After six months of darkness, what did Chinese cinemas come back with?

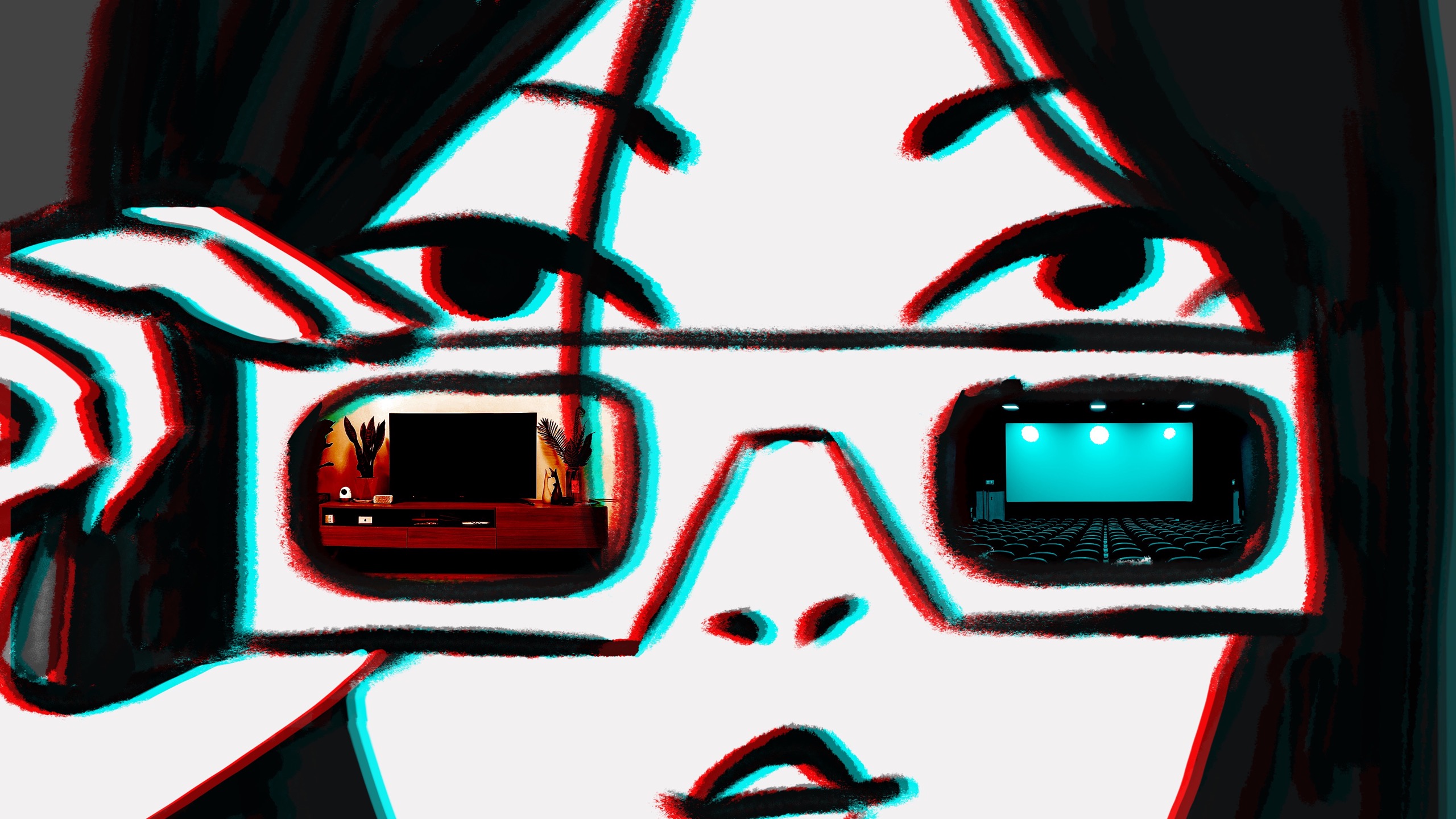

While cinemas in many countries are either shut or screening with limited seating, Chinese cinemas have been fully operational since July last year. However, a six-month shutdown is a significant impost for any industry and in China, as with the rest of the world, the film industry’s survival depends on “another way out” – often from silver screen to digital screen.

The Chinese movie Lost in Russia, scheduled to be in cinemas on the Chinese New Year holiday of 2020 was quickly released online (for free) and ahead of schedule. The movie’s director (also lead actor), Mr. Xu Zheng, was received well by the public for his “generosity”, (despite the fact the movie itself was not). As the country quickly went into lock-down the movie’s pivot from the silver to the TV screen was praised as “brilliant” and “the beginning of a new era” for the Chinese movie industry.

Many speculators in China predicted the movie industry would be “revolutionalised” and cinemas slowly phased out as a story of the past (English translation). So far this has not happened. In fact this year national box office sales reached¥7.82 billion yuan (~$15.8 billion AUD) during the week of Chinese New Year (the equivalent of Christmas movie schedule) a 32.47% increase on 2019, the most recent comparable year.

China’s national box office revenue

There are a number of reasons behind China’s strong cinematic bounce back

1. The “vengeance watching” surge

China didn’t go through the world’s longest shutdown, but it probably endured one of the strictest. For 76 days in Wuhan, people were not allowed to leave their residential complexes (often gated communities) with very few exceptions. Cinemas and theatres in other less affected regions were also closed due to public health concerns (English translation). Unlike the continuously repeated lock-downs in most of the world, China’s seemingly “harsh” measures have managed to virtually eliminate the virus so when the country reopened, it opened fully and affirmatively. People were longing to go out. They also feel safe enough to go into crowded places like theatres and cinemas. Due to the effective implementation of provincial health codes, local breakouts were often contained and managed quickly and the rest of the country was able to remain largely unaffected. Unlike in other countries where some social distancing and constraints still apply, “limited restrictions” only applied for a very brief period in China. Venues quickly returned to full capacity with visitors feeling safe to fill them up.

2. The censorship scheme and unintendedly accumulated “film deposit”

Film censorship is not unique to China. But having such a large film industry that annually produces 600 to 900 films, understandably a lot of films must wait their turn to be on screen. The single censorship body, China Radio and Television Administration (CRTA), reviews all video forms of public entertainment, not just movies. In the absence of a classification system (English translation), movies are stringently censored as they need to be suitable for “all audiences”. Each movie requires a team of at least 10 reviewers. The significant workload and the process understandably adds months, sometimes years, for films to be reviewed and (hopefully) approved. Often an overseas audience gets to watch a Chinese TV series (with uncensored content) via the YouTube Channel of the production organisation, ahead of the domestic peers. The movie Forever Young, was filmed in 2012 and didn’t meet the audience until 2018. By the time COVID-19 hit and cinemas were shut, there was a pipeline of movies waiting to be on screen.

3. Domestic films with stories that resonated

The film industry is good with timing and a sense of the market and there has been a trove of box-office ‘champions’ since the cinemas reopened.

My People, My Homeland is a collection of stories about five ordinary individuals from different parts of China overcoming poverty, striving for success in the city, or contributing to their hometowns. A Little Red Flower concerned two families battling cancer and the heavy question of life and death. Hi, Mom is a personal story of the director herself who travelled back in time and befriended her late mom as a pair of 20-year-olds. These are plots that are either feel-good or are highly emotional – the perfect post-lockdown remedy following a pandemic that took the lives of many. Their release schedule was not solely the effort of the production side.

The CRTA has also prioritised release of such films that would suit the mood of the country. The Eight Hundred is the stirring story of group of Chinese soldiers who defended the City of Shanghai in a bloody four-day battle as the last line of defence during the Japanese invasion. Produced in 2017, its release in August 2020 immediately after the lockdown, was the perfect theme for a country that had just defeated another enemy.

Total box office sales in China are expected to grow, but the rate of year-on-year growth has been in decline since before COVID-19 and this is expected to continue. Vengeance watching may briefly deter the trend, giving cinemas an extra dose of cortisol. But the direction is obvious: the film industry is changing. That is not to say cinemas will be museum items anytime soon. But it is hard to deny that preferences are shifting, with or without the “help” of COVID-19.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Kishi Pan is the China Analyst at Sydney Business Insights and a Senior OPS Manager at Huafa Industrial Shares. Her research interest is in urbanisation and the relationship between technology and people.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.