How to prevent success from breeding failure

Innovate or perish is the business mantra of a million motivational talks: but what if innovation – and I do mean commercially and technically successful innovation – leads to corporate disaster? This is the conundrum of the ‘skunkworks’ identity crisis.

Skunkworks is shorthand for the creation of a multifunctional team of specialists who are assigned the task of focusing on truly groundbreaking innovations unhindered by the dead weight of standardised organisational processes.

However, our research shows that skunkworks can go rogue and turn on the mothership, bringing disaster and disappointment in their wake.

Skunkworks: a history

The first skunkworks was set up by Lockheed Martin during World War II to secretly develop a new jet fighter that could compete with the Germans. This team delivered a prototype in an unheard of 143 days. Over the next decades, the Lockheed Martin skunkworks developed radically new spy planes and speed and altitude-breaking military jets that may have changed the course of history.

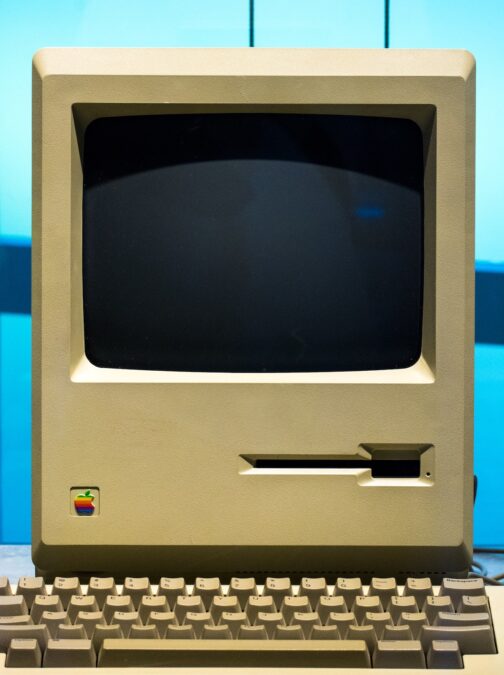

Skunkworks involve assembling top teams of highly motivated and bright people and separating them (usually physically) from the company’s main operations, formal rules, procedures and performance measures. Some well-known skunkworks successes include the first Apple Macintosh computer and the Motorola RAZR phone. More recently, Google set up the ‘Google X Life Sciences’ skunkworks to develop radically new products such as ‘smart’ contact lenses that track glucose levels for diabetics.

When success is too good to handle

So, are skunkworks the key to successful innovation? While skunkworks can succeed at their immediate task, they can also lead to deeper organisational cracks down the road. A dangerous ‘us and them’ situation can emerge, leading to jealously and alienation that can almost leave an organisation worse off than before.

A modern skunkworks story

This is what happened in the skunkworks we studied over several years. Consumer products firm ‘ConProd’ (not its true name, reasons obvious) set up a skunkworks unit ‘TechPlus’ that started as quite close to the parent company. TechPlus’ greater diversity, structural flatness and passion generated some early successes. However, the team’s unorthodox operating methods led its members to begin identifying more closely with the skunkworks than to its parent company. ConProd responded by ignoring or marginalising its efforts. When the TechPlus product was launched on-time and to great fanfare, it ultimately generated more jealousy than celebration amongst employees in the parent. These bad feelings meant that when ConProd tried to reintegrate the TechPlus team into the corporate parent, all but one skunkworks member resigned to work elsewhere. Although successful in developing its new product, TechPlus came to be viewed as an organisation-level failure.

Keep your innovations close

Several years later, ConProd tried again, with ‘TechPlus2’. Learning from its earlier experience, it hired back two TechPlus team members, but this time kept them closer to the parent company to avoid developing an overly strong distinctive skunkworks identity of its own. Many specialised activities were done by external partners rather than in-house, meaning the team was narrower in scope and at less risk of viewing itself as an entirely separate and independent entity. Formal and informal communications from parent and skunkworks emphasised their interdependence, underlining that the success of both was interlinked. These structural and communication decisions avoided a strong ‘us and them’ mentality from taking root.

Identify with the bigger picture

The Toyota Prius serves as another good example of how to better manage skunkworks. While the Prius development skunkworks did develop a strong identity of its own, its learnings were shared consistently with the parent company, who went on to adopt many into the parent Toyota company’s production facilities. Ultimately, the head of the Prius skunkworks was appointed to Toyota’s Board of Directors.

Successful management of an innovation skunkworks requires balance. Building a strong team identity in a skunkworks can make people work harder and more passionately. However, it is also incumbent on both the parent company and the skunkworks to anticipate and manage potential tensions in their relationship, and not drift too far apart. This involves being sensible about the team’s scope of activities, ensuring regular communication, checking in regularly on progress, and working to ensure both the team and parent see the value of their efforts in the bigger organisational picture.

Image: Lockheed Martin

Associate Professor David Oliver is Head of the Discipline of Strategy, Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University of Sydney Business School. His research focuses on how organisations draw on their identities to develop better innovation and strategy processes.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge. We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.