Georgina Macneil

Art and the AI machine

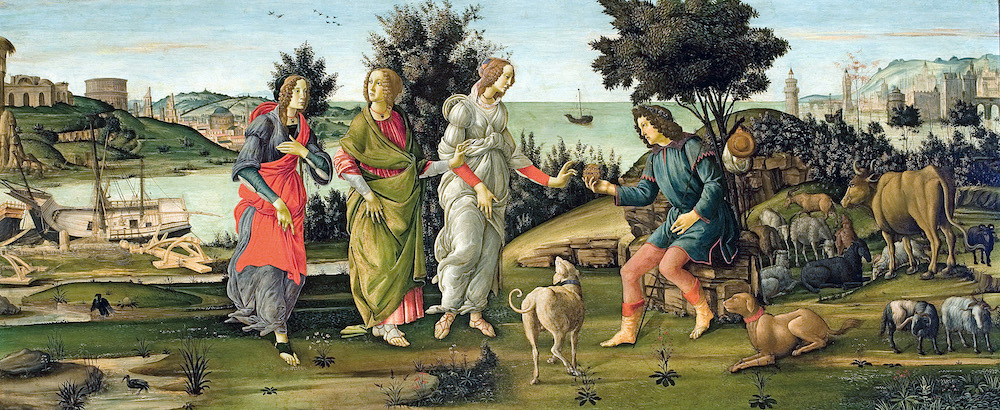

To my eye, Jason Allen’s recent AI-created work Théâtre D’opéra Spatial looks like a late 19th century French painting taking place on another planet – with clear influences of painters like Ingres and Delacroix who also gave viewers a window into a world alien to their own. However, the work continues to incite debate as to its artistic merit and the right of Allen to even assert authorship of this work.

In the ‘pro’ camp, Mike Seymour argues for an expanded understanding of the tools of art production in our machine-learning age. I find myself squarely in the same camp: not only is the artistic merit of this work clearly visible, but as an art historian trained in fifteenth century Italian religious paintings, I see the work as part of a trajectory of artists embracing new creative techniques.

In the ‘it ain’t art’ camp are those who argue that AI artist Allen didn’t do anything to produce this work: he didn’t paint, he didn’t chip into a huge hunk of marble, he didn’t undertake anything that the public recognises as creation.

The debate over where in the creation the artist’s actual work takes place, is an old one. Our modern conception of the starving artist passionately churning out canvases (think Vincent Van Gogh) is relatively recent. For hundreds of years, artists were more or less tradespeople, producing valuable consumer objects for wealthy patrons. There are exceptions (self-portraiture is a great example), but mainly artists produced the work they were engaged to produce with expectations contractually noted by their buyers.

In the 1400s in Italy it was well understood that what an art patron was paying for was not only the “toil” of the master, but rather, the skill of the master in conceiving a work and running the workshop which produced it. Revered old masters such as Raphael or Leonardo produced within the “studio” system. A master oversaw production, drew “cartoons” upon which more than one final painting might be based, mentored and taught assistants, and might complete specific parts of a painting themselves, or “by the master’s hand”.

In the 20th century, artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Carl Andre and Donald Judd – all well-recognised members of our established art canon – used “ready-made” or found materials to produce work where the labour of the artist was largely conceptual, rather than physical. Duchamp wrote of his output that the “art” he was creating was the reaction of the viewer – the viewer’s shock was his end goal, and the physical object was merely the vehicle which induced the viewer’s reaction.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CazKSrrs5SO/?hl=en

Artists such as Damien Hirst have contracted material experts to produce the works he conceives, as we don’t expect an artist to necessarily be an expert in shark preservation. To relitigate the idea that an artist has to produce something with their own hands leads us down a pointless road: what of the collage artist? Does a photographer have to develop their own prints, analogue-style? Does a painter have to grind and mix their own pigments for the finished work to be considered theirs? For many hundreds of years, buyers, critics and art historians have recognised that the intellectual work of the artist is where the true value of art lies.

Artists now explore digital media and experiential realms as a matter of course: Venezuelan multi-disciplinary artist Arca created soundscapes to accompany the digital mapping and visualisation of the Berlin region’s ancient swamp ecosystem in 2021’s Berl Berl, and then used extensive 3D technology in the clip for Prada / Rakata. New frontiers in art production include the blending of technology with the human body, and as these art forms spread, artists will more freely blur the boundaries between physical and virtual experiences. No doubt such experimentation, if and when it happens, will be ‘shocking’. One of art’s roles has always been to shock the viewer. Visceral reactions to art can include awe, religious terror, disgust, fear or fascination – the reaction itself is always the key.

Every new technology represents a fresh frontier into which art can evolve, as human experience also evolves. The study of art history is the study of the visual output of a culture, and as such, AI art deserves its place in the history of our art and times. Not all controversial art is automatically good art – but a lot of the art we now consider to have self-evident worth was controversial art when it was created. I look forward to watching how artists will use this new art form to challenge us.

In the spirit of this argument… Artist Steven Sommer generated the hero image for this article using Stable Diffusion with the prompt “A star orbiting a black hole, style of Eugène Delacroix, masterpiece 4k digital illustration, highly detailed, award winning”

Dr Georgina Macneil is an art and pop visual culture commentator who completed her PhD in fifteenth century Italian art history at the University of Sydney. Her recent work focuses on the use of traditional art historical tropes in contemporary video clips such as Lil Nas X’s MONTERO.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.