Sandra Peter, Kai Riemer and Adam Kamradt-Scott

COVID-19, airlines and business continuity on The Future, This Week

This week: COVID-19 grounds airlines, and business continuity learnings. Sandra Peter (Sydney Business Insights) and Kai Riemer (Digital Disruption Research Group) meet once a week to put their own spin on news that is impacting the future of business in The Future, This Week.

Our guest: pandemic expert Associate Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott from the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.

Please note: our numbers regarding cases of COVID-19 and countries affected were accurate at the time of recording. Please check here for up to date information on cases and countries affected.

The stories this week

00:45 – Our guest Adam Kamradt-Scott on the business of pandemic response

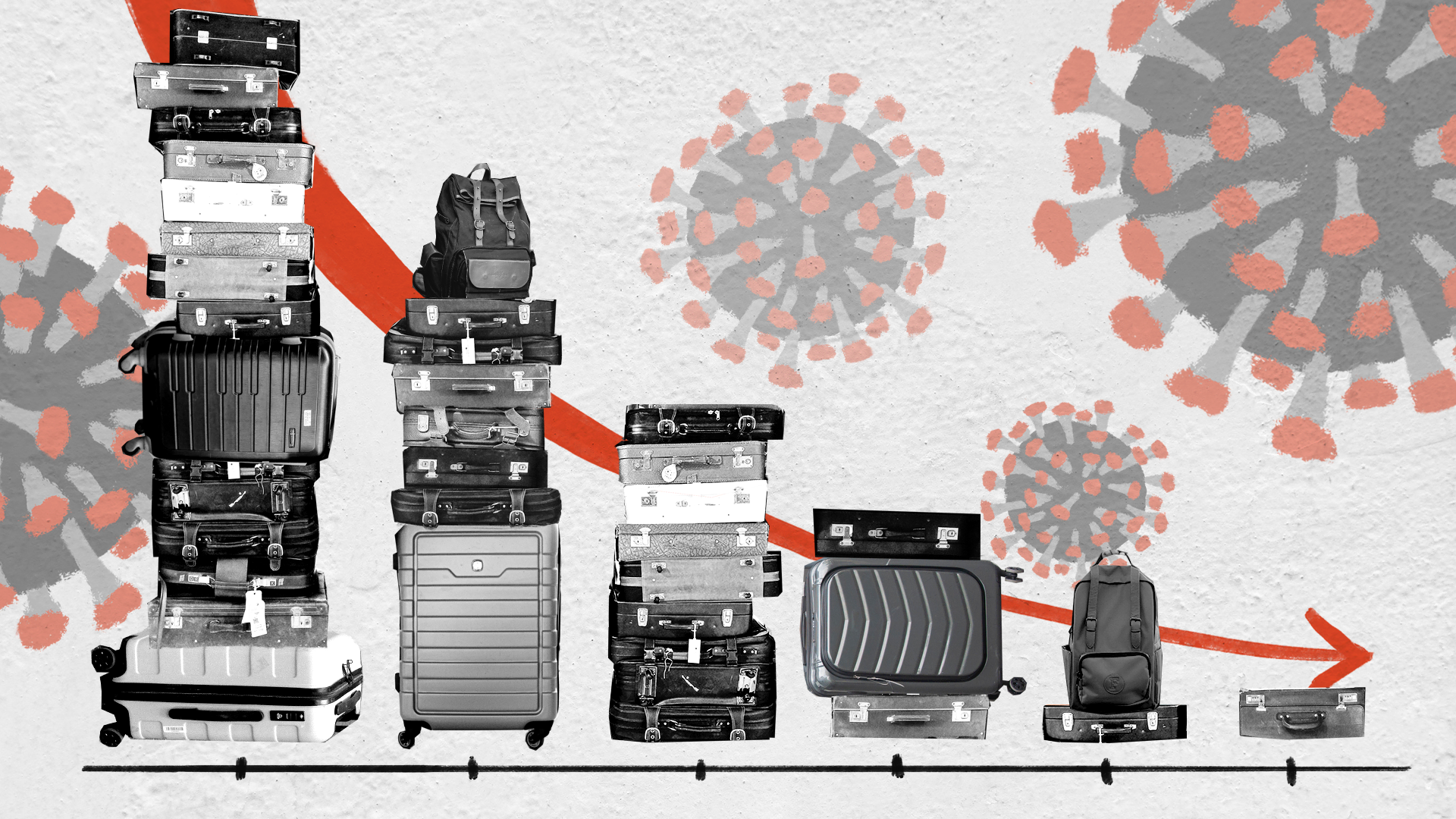

09:14 – Australian airlines will suspend all international travel

26:23 – What else will have to change after COVID-19?

Other stories we bring up

Virgin Australia suspends its fleet

The Australian aviation industry to receive a $715m relief package

Corona grounds flights around the world (numbers)

The aviation industry may not fully recover from the effects of the pandemic

To stop coronavirus we will need to change almost everything we do

How food delivery drivers manage to work in China despite coronavirus

Cross-industry redeployment of staff during the crisis

World Health Organization’s influenza information site

You can subscribe to this podcast on iTunes, Spotify, Soundcloud, Stitcher, Libsyn, YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts. You can follow us online on Flipboard, Twitter, or sbi.sydney.edu.au.

Our theme music was composed and played by Linsey Pollak.

Send us your news ideas to sbi@sydney.edu.au.

Dr Sandra Peter is the Director of Sydney Executive Plus and Associate Professor at the University of Sydney Business School. Her research and practice focuses on engaging with the future in productive ways, and the impact of emerging technologies on business and society.

Kai Riemer is Professor of Information Technology and Organisation, and Director of Sydney Executive Plus at the University of Sydney Business School. Kai's research interest is in Disruptive Technologies, Enterprise Social Media, Virtual Work, Collaborative Technologies and the Philosophy of Technology.

Adam is an Associate Professor at the University of Sydney and specialises in global health security and international relations.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.

Transcript

This transcript is the product of an artificial intelligence - human collaboration. Any mistakes are the human's fault. (Just saying. Accurately yours, AI)

Disclaimer We'd like to advise that the following programme may contain real news, occasional philosophy and ideas that may offend some listeners.

Intro This is The Future, This Week on Sydney Business Insights. I'm Sandra Peter, and I'm Kai Riemer. Every week we get together and look at the news of the week. We discuss technology, the future of business, the weird and the wonderful, and things that change the world. Okay, let's start. Let's start!

Kai Today on The Future, This Week: COVID-19 grounds airlines, and business continuity learnings.

Sandra I'm Sandra Peter, I'm the Director of Sydney Business Insights.

Kai I'm Kai Riemer, professor at the Business School and leader of the Digital Disruption Research Group. Since it first appeared in Wuhan, China just three months ago COVID-19, has spread to 165 countries, but it's been a long time coming. The World Health Organization has been predicting an influenza pandemic since it was formed in 1948. For the next 50 years, Australia was largely complacent and dangerously unprepared for the hypothetical problems raised by the spread of a contagious and untreatable disease. In 2006 and again in 2008, the Prime Minister's department assembled a high-level team of experts to stress test the nation's health services and essential infrastructure. The lessons learned from these exercises formed the protocols set out in Australia's National Action Plan for Human Influenza Pandemic, a whole of government coordination plan binding every state and federal government.

Sandra Our guest today, Associate Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott, was one of the experts involved in testing Australia's readiness for a flu pandemic. Adam is an internationally regarded expert in Global Health Security. He is from the Department of Government and International Relations here at the University of Sydney. And we are really pleased to be able to have you at such a time. I am guessing the last few weeks have been pretty hectic for you Adam.

Adam Yes, it's been quite a ride over the last two months already, actually, since the outbreak was first announced.

Sandra We're hoping to talk to you a little bit today about what is the business of managing a response to a pandemic, and in particular to the corona response, given the work that you've done, not only as a researcher, but also your work with government and with the World Health Organization?

Adam Well, I think probably one of the first things to appreciate about pandemic preparedness really is that it's unlike any other type of disaster. So whereas if you have something like an earthquake or a flood, you have the event and then government immediately then goes into the recovery-phase. With a pandemic you could be confronted with multiple waves of a pathogen spreading. And so it becomes quite challenging for government and other actors to know exactly when to institute the recovery phase of responding to these types of events. And it's for those reasons that, particularly Australia's pandemic plans, we ended up developing them in such a way to allow for nuance, in anticipation that one part of the country may still be affected, while another one may be starting to recover, and we need to try and encourage that recovery as soon as possible. So, yes, it's quite a challenge beyond your standard sort of natural disaster type arrangement.

Kai So Adam, on The Future, This Week here we are interested in the future of business, also the future of technology. We're not a health or medical podcast, so we're going to stay clear of the, you know, medical advice apart from, yes, you should be washing your hands regularly and often and much more often than usual. What we're interested in is looking at the business and organisation of how we actually deal with a pandemic like this. And so maybe we start by you telling us about your role in all of this, and then we sort of unpack what it looks like behind the scenes as Australia grapples with this unfolding disaster.

Adam Sure. So I think it's probably important to appreciate, at least for the Australian context, the WHO released its first pandemic preparedness plan in 1999, and the Australian government started to look at our pandemic plans not long after that. In 2006, the Australian government held the first national exercise program to look at the health sector impacts. And that was Exercise Cumpston in 2006, and that was a real world exercise. So they basically had a simulation of a plane landing in Brisbane Airport and they engaged a whole lot of actors to act as if they were sick and unwell, and then mobilised the health sector response. After that exercise was concluded, the Council of Australian Governments decided that it was important for us to also then look and explore the non-health sector impacts. And so a decision was taken to then hold a second national exercise, which became known as Exercise Sustain 08. And I was at that point in time working for the Australian government and were seconded to the task force to help run and organise that national exercise program. So that exercise program held three discussion exercises and a functional, or real-world, simulation, looking at the conversations that have to be held at government for whole-of-government coordination. A lot of my experience in the pandemic planning side of things, and particularly looking at business continuity and response and recovery in these types of situations is derived from that experience. But after working in that role, I was then offered a position over at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and I have continued to remain in academia since that time, although I'm working closely with the government at the moment, again around health security related matters.

Sandra If we're looking at the non-health response, what would that look like? What's the structure behind the scenes?

Adam So I think that it's probably important to appreciate there's obviously different phases to this, and particularly since 2005. And you may recall the spread of H5N1 or bird flu coming so close as it did after the SARS outbreak in 2003. There was a lot of concern that bird flu may instigate a global pandemic. We're very fortunate there, though, because that virus didn't achieve effective human to human transmission. And so we didn't end up seeing the spread of that virus to humans worldwide. But nonetheless, as a result of that concern around the spread of H5N1, the government certainly encouraged companies, the private sector, as well as other segments of society, civil society and elsewhere to really look at developing pandemic preparedness plans. The difficulty that has risen since that time, and there was a lot of anxiety obviously between 2005 and 2009, but when we then had the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, we found on the other side of that there was a lot of pandemic fatigue. Basically, people were very tired of talking about the possibility of an influenza pandemic. And so for many companies out there in the private sector, we're conscious of the fact that they may not have looked closely at their preparedness plans for a full decade. And unfortunately, now we're in a situation where it's kind of too late to then go back and revisit those because we're now in a real world response. And I think at this point now, the focus really has to shift to how do businesses continue to provide services to remain viable, and also to ensure that they're able to recover on the other side of this event. The good news is COVID-19 will go away at some point, we just don't know exactly when it will stop causing global challenge.

Kai Adam, when you say 'the government', who are we talking about? Who are the people or entities in government that are coordinating our response? Who's making the decisions, who is deploying resources?

Adam So under the plans that the Australian government have developed, we're slightly different from a number of countries around the world in that we are a federation. That presents challenges as well as some potential benefits, but particularly challenges when it comes to coordination. So under the plans that were developed and finalized back in 2008, our arrangements are that the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet provides the whole-of-government coordination mechanism, but then the federal Department of Health provides the technical lead agency. So our federal Department of Health basically then coordinates with state and Territory Departments of Health, which are obviously the responders. So the federal government doesn't have its own independent health workforce that we can deploy to help states and territories. So it really comes down to the states and territories. And under the federation arrangement, it states and territories that are responsible for the delivery of healthcare services and ensuring those services are fit for purpose. So our federal government has a coordination role. The lead technical agency in that role is the Department of Health. But then it is through close collaboration with our states and territories that the response to any sort of disease outbreak or major threat like a pandemic, is coordinated.

Sandra Most of the plans for responding to flu pandemics were developed more than 10 years ago. But one of the big changes since 10 years ago is that there is a lot more international travel, a lot more flying around the world. And it's actually one of the first articles we wanted to discuss today, which has the impact on airlines and in particular in Australia. We've seen Qantas and Jetstar initially slash 90 percent of their international flights. Now, Qantas, Jetstar and Virgin saying they're going to slash all of their international flights due to the coronavirus. Also, Qantas putting on standby two thirds of their workforce. How do we think about the impact on airlines?

Adam This is obviously going to be probably one of the biggest challenges worldwide that we will confront as a result of COVID-19 spread. Obviously, as the virus has moved from China to other parts of the world, we've seen a progressive rollout of cancellations of flights. And that's a combination of both governments encouraging airlines to either cease or reduce operations, as well as a significant drop in demand for people flying, because of concerns around the virus. So obviously, the airline industry is part of our critical infrastructure, particularly in countries like Australia when we have such major distances to cover. So it's really critical that these critical services are able to continue to remain viable once this event is over. And so it's a matter of how those companies ensure that. Of course, part of the challenge associated with this as well, and particularly the cancellation of all international travel, that will now also present a challenge for us in Australia in how we try and provide assistance to our neighbours. So the Australian government has, for a number of weeks now, been mobilizing our experts to help go to other countries to help them prepare for the arrival of COVID-19 cases in their jurisdiction.

Kai I mean, this is an interesting aspect, right? The virus has spread because we're such a global community. We're so used to just going everywhere in the world. Now we're seeing these responses largely in a very national protectionist manner. Everyone closes their border to curb the spread of the virus, which is actually a good response. But now we're risking basically everyone for themselves. And we've just seen that China has deployed medical experts and equipment to Italy to help out. But once we shut down all international travel, that will become harder to organise these swift responses. So what is the international aspect of fighting the response and can it do without travel? Can we do this all digitally now?

Adam Ah, unfortunately no, we can't do this all digitally. There's a number of countries that don't have sufficiently advanced healthcare systems is what Australia does. And we really benefit from having a universal health system and having really highly skilled, trained health professionals as well. And they are obviously on the frontline, and we need to probably acknowledge and thank them for their service because they're going to face a very challenging period over the next couple of months. And obviously they've got families and loved ones that they look after and care for as well, so this is going to place a considerable strain on them. But for many other countries, they don't have even basic health care services and they certainly don't have universal health systems anywhere near the type of system and level that we have in Australia. And so it's really important for us to be mindful of that. This is a situation where we are facing a collective threat and it's really important that we also respond collectively. And you're right that it has been one of these phenomenon that we've seen is that countries closing down borders, calling citizens home, basically everyone sort of reverting internally to look after themselves. It's really important for us in Australia to appreciate, though, we may be able to get a good handle on the outbreak here and resume sort of level of normalcy with our lives, maybe sooner than what other countries will, but are also very contingent on what other countries do,.

Kai We're very used to coordinating in bushfire disasters, for example, because, you know, that happened much more frequently, were collaborating with Canada and the US, we're exchanging equipment and people. Are there any official plans for how nations help each other out in a pandemic or is it up to the WHO or to co-ordinate this? How does that work?

Adam WHO has the mandate of being the lead coordinating authority in these types of events. But like our federal government, the WHO doesn't have a dedicated workforce that it can deploy to countries. So it relies on countries volunteering experts to help out other countries. And it provides a coordination mechanism to help facilitate that. But it doesn't have large numbers of technical experts that it can deploy itself, which obviously then also creates a bit of a workforce challenge. We don't have a formal agreement as to how governments co-operate in these environments. We do have an international framework which helps guide and direct what countries should do in these situations. And it's called the International Health Regulations. That framework provides a basis for which countries can put in place measures to help protect their populations. But it is also designed to meet a very delicate balance between preventing the international spread of disease while also minimising unnecessary disruption to international traffic and trade. And that's an important balance to strike because obviously economic issues can have other long-lasting unintended impacts on health as well. So if people lose their jobs, for instance, as a result of the spread of the coronavirus, they may not then be able to provide for their families, be able to access good food, and so their nutrition starts to suffer, leading to either long-term or even short-term adverse health outcomes. So I understand at the moment there's a lot of focus, obviously we want to stop the spread of this virus, but we also do need to be mindful about the global economy, because it's going to be that which can have potentially even longer-term impacts around the health of populations all around the world.

Kai Looking at these impacts more long-term, do you think we need better concrete, collaborative arrangements to prepare for future pandemics as an outcome of this?

Adam There's no question that we do. The challenge that we confront in this area is that you find countries often assert their sovereignty when it comes to health systems and how they are structured. So we see a tremendous difference, for instance, between countries like Australia and the United Kingdom, which have universal health cover systems versus other countries like the United States, which operates on a user-pays system. And in that context, it influences then how countries respond domestically. And we have found in the past that countries are very reluctant to be told what to do by an international organisation, as you can appreciate. And so they often resist any sort of very structured international framework. And it's for this reason that the International Health Regulations, it provides guidelines for what countries should do. But we don't have enforcement mechanisms, nor do we have a penalty for when countries do the wrong thing. And if we contrast that with the World Trade Organisation, which obviously can fine countries, if they're found to be doing the wrong thing, then it arguably does present something for us to look at in the future as to whether or not we need to try and strengthen those arrangements.

Sandra One of the arguments that's been made is that the aviation industry might not ever fully recover from the effects of this pandemic. We've seen the Australian aviation industry will now receive a, I think it's 750 million dollar relief package from the federal government. But through the effects that we're already seeing, that's probably not going to being nearly enough to keep some of the companies afloat, Alan Joyce said it's survival of the fittest. Same thing in Europe with Virgin Atlantic, with major hub airports being hit in Germany and France, in the Netherlands, passengers not flying so follow-on effects from that.

Kai Yeah, let's remember that the airports in Australia, are also private corporations who are quite dependent on the air travel to make an income, as well as all the businesses inside the airports which are also impacted.

Sandra So how do we think it's best to balance out the need for some air travel to continue, and especially, as you've mentioned, the unintended consequences and the implications on being able to have an international response through moving experts around, but also through the follow-on effects on airports, on cities that will have no workforce. How do we think about the response in the airline industry?

Adam I think this all again comes back down to business continuity planning and the extent to which these businesses have gone through that process to identify how they can continue to remain viable. So obviously, the airports are a really interesting example. They have one provider effectively, which is airlines. And so in that context, being able to work out what is the best way for them to continue business operations or are they going to have to suspend for a time? What does that mean for their workforce? Because you can appreciate if you suddenly find yourself unemployed, you're then going to look elsewhere for a job as soon as you can because you may have a mortgage, or family to feed, or even just yourself. So we've seen in the past that once you lose certain skillsets, they're very difficult to recover. Let me perhaps go back to an example that we were looking at in the national exercise program. So at one point we were discussing the need potentially to look at instituting widespread quarantine. One of the issues which immediately arose is that we have a responsibility to ensure that people, if we are putting them into forcible quarantine, that they need to ensure that we provide them with food and other basic necessities. And when we were doing this planning initially in 2008, we didn't have home delivery services like we do now through the major supermarket chains. In fact, what we identified was that we only had a few non-government organisations that were small scale and it wasn't clear that we would be able to see them mobilise and expand their services to meet the demand that would inevitably grow. And so at that point we then engaged with the major supermarket chains to have a conversation with them about how could we ensure that we would get food delivered to different locations and also allow other people to access supermarkets in the event of widespread lockdowns. Fortunately, now, 10 years on, we have the major supermarket chains that have put in place home delivery services, which now starts to provide some level of mitigation of that need. Obviously, it will be tested in the event we do end up in a widespread lockdown. But nonetheless, there is a much greater capacity now than what there was beforehand. Similarly with airlines. So when it comes to the essential services that they rely on, obviously aeroplanes are very technical pieces of equipment. And so we have very skilled engineers that ensure the safety of those aircraft. If those engineers are suddenly laid off and found that they're no longer employed, understandably they would look for alternative employment in the event this is all over, then our airlines may want their staff to come back. But of course, the staff may very well say, 'well, actually, you know what? You weren't there for us. So we found alternative work and we're quite happy now. Thank you very much'. And so that then has other long lasting long-term impacts that were perhaps unanticipated. So in these types of environments, it's really important that each business really considers its business model, that it identifies what are the critical elements to keep that business operational. It's fine to institute temporary lockdowns or temporary close-downs, but what happens to the staff and that critical expertise that they require to keep their business operating? And I think it's going to be really important for those businesses that are taking these measures, like Qantas, like Virgin and other airlines. If they're stopping services, that they obviously want to continue to ensure that they retain that critical knowledge and expertise that keeps their businesses operational and which will allow them to then recommence operations as soon as practicable.

Kai That's really interesting, Adam. We've seen an article a couple of weeks ago about Wuhan, where the point was made that the delivery services that have been quite prevalent in China for a long time and has grown off the back of the digital technology and ordering through WeChat and apps have actually kept the city afloat during the total lockdown, right. So people on their mopeds delivering food to people has been the backbone infrastructure that actually made it possible to react to this pandemic in that way. So that's a really interesting aspect, which I think we're not quite there yet in Australia, but we're in the fortunate position that we do have, especially in the cities, now Uber Eats, Menulog and also the supermarkets delivering. The other thing is the interesting aspect of skills, right. So I can see the point of companies needing to keep their skilled workforce beyond this pandemic, even though they might not be able to pay their wages at this point. But there's also now this whole fluctuation of skills shortages. We've just seen Amazon in the US announcing that they have to hire 100000 additional warehouse workers to cope with the demand for online delivery because people obviously don't want to go to shops. So that's a...

Sandra Hopefully not airline engineers.

Kai Yeah, well, that's the point, right? But people will basically, in this situation, take on any work that they can to make do. So it's a real interesting employment effect here.

Adam Sometimes, obviously, there are consequences and outcomes that we don't even anticipate. You know, Amazon, as a good example, has been working obviously for a number of years to full automation of delivery services. And so now it's interesting then that at a critical juncture, it may be that even those automated services are insufficient to meet the demand. And so suddenly then a major company is required to then go through this process of looking to appoint hundreds more staff to be able to meet that need. And this, again, that goes to that critical element of business continuity planning. So thinking about where are the vulnerabilities in the business, what are the elements that are going to have the most significant impact? It was fascinating when we were going through these exercises and planning, talking with businesses about what their business model was and how it was that they conducted their business. And we found that oftentimes companies would think about the first-order impacts, the immediate things. So we were talking to them about, for instance, how do you continue to provide your business operations if you have 40 percent absenteeism from staff becoming unwell? And then they would, you know, go through the planning process as to what they then needed to close down, and what they needed to continue to provide in order to maintain their business model. We were like, well what happens then if your suppliers have this complication, if you're reliant on the supplier for a product or service and they encounter this problem? And it was often found that once we looked at the second, third, fourth-order impacts, that potentially could emerge, businesses hadn't thought through those consequences yet. So that's one of the real important elements around this whole process of business continuity, you can't just look at what are the immediate impacts on your workforce. You have to also consider who are the people in the other businesses that we rely on to deliver our business? And have they had conversations with them prior to a crisis to work out those arrangements? Unfortunately, now we're obviously in a situation where we're in the middle of it, and it may be a little bit too late to have those types of conversations. This has been one of the big challenges that we've seen now for a number of decades in dealing with health crises like pandemics. We've had this constant cycle of panic and then neglect. So once a crisis happens, everyone panics about it, tries to work out what to do, but then as soon as it's over, everyone then just goes back to normal and forgets about the implications or the challenges that they were confronted with. And we need to get out of that cycle of panic and neglect.

Sandra Speaking of panic and neglect, there was another story we wanted to bring up today about how this latest pandemic will change the way we travel and the way we work and the way we do business. It was a Bloomberg article that we'll put in the shownotes. Because that is the question., will this have a lasting legacy in how we behave or how we conduct business or even how we travel, how we work remotely? Or is this another one of those cases of, you know, panic and neglect?

Adam It is a really interesting question. This is the first time that we've confronted something on this scale. And just to put it in context, I believe even the prime minister has made reference to the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, which is when Australia last confronted something on this sort of scale, and the international community. Talking with some government officials already, they have made the observation that this is going to have long-lasting impacts and it is going to change the way we live. I'm a little more cynical, in that having been an observer for more than a couple of decades of this space, we have seen in the past that people try and move past the trauma of these events as quickly as they can. And sometimes that means forgetting the lessons that need to be learned. So I am certainly hopeful that this will help us shift out of this whole cycle of panic and neglect. But a good example, again, could be something like universal health cover. So this has been something that the World Health organisation has been pushing for a number of years and really advocating for countries to move towards those systems. But there's strong ideological opposition to universal health cover in a number of countries around the world, no least which being America.

Sandra You mentioned the US as an example there, but governments are already struggling to spend more on health, and there is a massive cost associated with the epidemic itself. So the US will be spending enormous amounts of money just dealing with the effects of the pandemic and then the flow-on effects from that. Can countries or even the global community then find both the political will and the financial resources to invest in something like a universal health cover?

Adam Obviously, issues around universal health cover, those services are usually provided through taxation. Various different countries have different arrangements for collecting things like tax, which are obviously really important to be able to then provide services back to communities. So do we have the political will and economic means? The political will, I think is probably the biggest question. And if there are going to be lasting changes after this event, it's really going to have to be led by the politicians. And that also, to some extent, has to be led through public pressure. So at the end of this, and when we're looking at COVID-19 in the six, 12 months after it's all over, it will be really critical for populations to send very clear messages to their leaders as to how they want their society restructured after this is over, the economic means will then flow. So a good example, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014. It was interesting to me coming from a country like Australia, where we obviously have a fairly significant tax rate as well as a very comprehensive means of collecting that tax, that you go to a number of low and middle-income countries and they don't have those systems in place. So this then impacts the government's ability to provide those types of services. In the aftermath of COVID-19, those countries in particular need to probably sit down and make a decision themselves as to what are the costs and benefits of implementing systems such as universal health cover. Is this something that they now place value on as a result of their experience from COVID-19? Or are they going to continue the way that they have been?

Sandra Does it depend to some extent on the economic impact rather than the health impacts? I mean, the Great Depression did start the welfare state. Will universal health care be the result of a huge economic impact from the coronavirus?

Kai And not necessarily just to provide care for everyone as the immediate outcome, but also to be able to respond as a country, as a system, to the pandemic, because we're creating incentives for people to see the doctor, because we're reducing the out-of-pocket cost. We might have the ability for people to access paid leave in the event of sickness, and all of these kind of things that incentivize people actually present to the authorities or to the health system with the disease so we can test and track and reduce the spread of the disease.

Adam Well, those of us that work in global health certainly hope that this is one of the outcomes, is that we would see that move towards universal health cover. Because in being able to respond in a crisis, you've got to have the systems in place there in peacetime. And the analogy of war has already emerged a number of times in talking about COVID-19. but it's quite an appropriate analogy. The systems that we rely on to conduct disease surveillance, to test people for the presence of the virus, and then having the means to respond to people being sick and unwell, requires and necessitates a measure of a health care system with certain basic elements already in place. And you can't build those elements in the middle of a crisis. They have to be there beforehand. I think that would possibly be one of the best outcomes that could come from this pandemic, would be that countries more broadly would then start to look at the benefit of the universal health systems. Even Dr Tedros, the Director-General of the World Health Organization, has talked about health security and universal health cover being two sides of the same coin.

Sandra Speaking of response, we spoke now a bit about government's response. What should businesses do? So from the work that you have done, whether that's work for preparedness or for acting, what should businesses more broadly do and in particular, what should happen in the airline industry at the moment?

Kai So taking the position of this is going down now, we have to respond immediately. But it also presents an opportunity to learn from this and to prepare for future events of that nature. So what can we take away from this? What should we do now to actually get this learning in place?

Adam Well, hopefully businesses have already thought through some of the implications around continuity planning before this outbreak and now pandemic. If they haven't done that already, particularly in Australia, where we haven't seen widespread community spread like we have in a number of European countries and in China, we have time at the moment to do an analysis of each business, to look at where are the critical vulnerabilities to the ongoing viability of that business. And it doesn't take much to go through that process. It literally can be done over a couple of days. And I think people should use this time productively at the moment, before we're confronted with potential more stringent measures, to take this opportunity to have those conversations and to think about those second, third, fourth-order impacts, which may have an unintended adverse impact on business operations. And from there, then start to prepare. Because we've been able to slow the spread of the coronavirus within Australia, and that the majority of our cases continue to be imported, that's given us time. And we need to use that time productively to think about those sorts of measures and impacts. In terms of the lessons learned, it's really then a matter of making sure that these types of issues are documented somewhere, and that when businesses are able to resume normal operations and many of them will. Unfortunately, we anticipate that many businesses, this pandemic will be a fatal blow. And that's obviously extremely regrettable. So for those businesses that are able to resume operations, to make sure that these processes that they went through to identify the critical viabilities, or the critical vulnerabilities, are captured, recorded and that they're revisited in future on a regular basis to avoid this cycle of panic and neglect. Those are really critical.

Sandra We're seeing a lot of attention being paid for instance to large businesses, such as airlines, but a lot less attention to what small businesses could do. Not what an airport can do, but what a little coffee shop can do, in case of something like this. And whilst many of the large companies might have some systems in place or some way of organising to go through the impacts, or try to put in place business continuity plans, many of the smaller businesses don't. Is there something that you could advise, in the case of a smaller company or for a small or medium enterprise of what they could do?

Adam I'll come to that after addressing the issue around the airline industry that you raised in the previous question. So airlines and airports are considered part of Australia's critical infrastructure. For a number of years these industries have really sort of walked a bit of a knife's edge between increasing costs of aeroplane fuel vs. the costs that they charge for international flights and so forth. So they've walked a very fine line for a number of years, which has also meant that the cash reserves may not be as wholesome as what some other businesses may have. But because of the nature and the fact that they are critical infrastructure, it also means that we need them to survive. And so I anticipate that you would expect to see that the government will continue to provide financial incentives to keep those critical elements of infrastructure continuing to function and survive. I think you're right that one of the biggest challenges really comes down to the small and medium enterprises, the family-owned businesses, that are confronting a massive falloff in business demand, and they may be employing a number of staff and maybe employing their family even. And it's those businesses potentially that are going to struggle the most in this current environment. I guess there's a call for all of us that we continue to support businesses as much as we can throughout this time. It is an element that we are literally all in this together, and we need to get through it together. While we don't want people to engage in panic-buying, we obviously want people to continue to buy, and to continue to spend money, so that the economy will continue to progress and move.

Kai So, Adam, thanks a lot for talking to us about the implications for businesses, for government, health systems, what people can do. I was just wondering, the National Action Plan, what does it say about coming out the other end of this, the recovery phase? Is it too early to talk about this, or can we look forward a little bit to say how can we bounce back from this?

Adam It's certainly not too early to be talking about recovery. We know that the pandemic will only last for a certain amount of time. The problem at the moment, obviously, is we don't know how long that is, it's kind of like how long is a piece of string, really. But businesses need to be prepared and be on the front foot for recovery, and to be able to re-scale up. Obviously, at the moment, we've got a number of businesses that are scaling down their operations to cost-save and reduce demand for services as demand has reduced. And obviously with that reduced cost focus. But we also then need to start to think about how do we then re-initiate our business model. It's much easier if businesses have retained their staff throughout this period. And while we're looking that this is going to be more than just a couple of weeks, it's likely to go on for a number of months, businesses need to make sure that if they are letting staff go, they're not letting staff that are critical to their business go, during this period. And this is one of those situations where hopefully businesses have got some cash reserves because we're in that rainy day. Today is the rainy day. And in that context, continuing to employ workers, ensure that they can continue to feed their families is really critical not only to businesses being able to recover, but also wider society. So I guess there's a bit of a plea there on my behalf to business leaders to make sure that whatever decisions they take with regards to closing down operations and reducing services at the moment, is that because we're all in this together, that they also think about this as a bit of a service to the wider community. It's important also that businesses ask for help if they need it. And there's a number of different resources that we can call upon. We obviously have professional associations that serve as lobby groups for government and being able to get together collectively to identify those sectors of society that are really struggling, and to get them to work collectively to call on government, potentially for financial packages and assistance, is really one measure that they could look at. The other important thing is, we all have access to our political leaders, so we all have the ability to write to our members and senators and to highlight the human cost of this. It's often easy when we're talking about events like natural disasters and including pandemics that we focus on how many people have died, what have been the health impacts and consequences, without thinking about the other elements of the human story, the people that are really struggling to feed their families and so on. So we need to make sure that we can make people aware of those human impact stories. And if you need help, ask for it.

Sandra Adam, thank you so much for talking to us today. We here at the University of Sydney Business School and Sydney Business Insights, we are putting together a repository for businesses, individuals for business leaders, for community to think through the impacts on businesses and to make sure that we can come out the other end, even though the rainy day is today. Thank you so much for talking to us today.

Adam Thank you so much.

Kai Thanks, Adam.

Sandra And that's all we have time for today.

Kai See you soon.

Sandra On The Future...

Kai Next week.

Sandra This week?

Kai Yes. But next week.

Sandra On The Future, This Week. Next week. Thanks for listening.

Kai Thanks for listening.

Outro This was The Future, This Week, made possible by the Sydney Business Insights team and members of the Digital Disruption Research Group. And every week right here with us, our sound editor Megan Wedge, who makes us sound good and keeps us honest. Our theme music was composed and played live on a set of garden hoses by Linsey Pollak. You can subscribe to this podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Spotify, YouTube, SoundCloud or wherever you get your podcasts. You can follow us online on Flipboard, Twitter or sbi.sydney.edu.au If you have any news that you want us to discuss, please send them to sbi@sydney.edu.au

Close transcript

- Business impact, Industry impact

- Airlines, Business model, Coronavirus, COVID and industries, COVID and strategy, COVID and supply chains, COVID and work, COVID-19, Food production, Food security, Future of business, Future of healthcare, Health, Healthcare, Podcast, Remote work, TFTW, The Future This Week