SDGs by 2030 – are we on track?

Decent work, not there yet for Australian women

Women’s work – to turn the language of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 around – is indecent work.

We can’t tackle ‘decent work for all’ without adopting a gender lens because it is women who do the majority of poor-quality work both in Australia and globally. Casual, low paid, dangerous work is ‘women’s’ work’. Some of the most highly feminised sectors are those where job quality is the poorest. Decent work, according to the International Labour Organisation, is about fair rates of pay, a living wage, having a voice at work, equitable treatment and security of employment.

My research focuses on the ‘decent work for all’ aspect of SDG 8. I am very interested in the intersection of decent work and gender equality (SDG 5). If a gender lens is not applied to the concept of decent work, we won’t have a full picture of labour market dynamics nor are we able to identify pathways to better practice. I explore how the labour market operates as an ‘architecture of disadvantage and difference’ shaping career progression, wellbeing and economic security. Along with my research colleagues I have identified seven dimensions of gendered inequality at work in Australia. Each of these dimensions drives very different labour market experiences and outcomes for workers on a gender basis.

- Vertical labour market stratification

- Horizontal labour market segmentation

- Undervaluation of feminised work

- Discrimination and disrespect

- Insecurity and precarity

- Working hours disparities

- Gendered division of unpaid labour

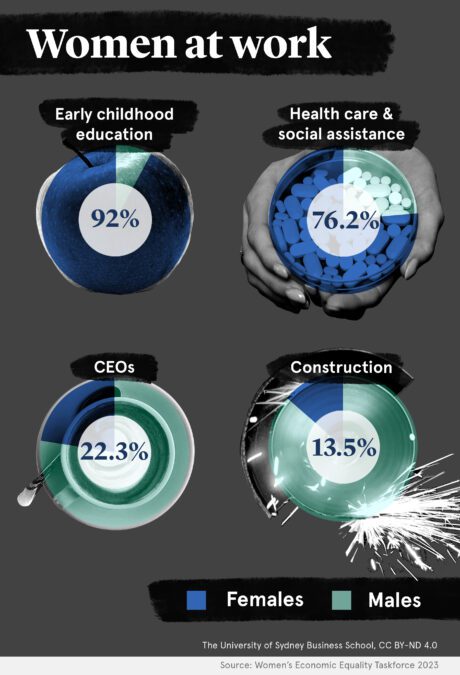

Australia’s workforce is highly stratified and segregated by gender. (Vertical labour market stratification; Horizontal labour market segmentation ).

So-called ‘women’s work’ (in health care and social assistance, education, retail, hospitality and tourism) is valued and paid less than male dominated jobs (construction, mining, manufacturing, transport, tech). In highly feminised areas of work, payrates are lower especially at entry level, job classification structures are much flatter (meaning fewer chances to ascend to higher pay rates), and employment is more precarious and more dangerous. (Undervaluation of feminised work; Insecurity and precarity).

Decent work also offers employees a ‘voice’ in the workplace. (Discrimination and disrespect).

Voice is about having the capacity to influence what happens in your workplace. In highly male dominated sectors, workers report having high levels of voice: they feel listened to and consulted by their managers. Workers (both male and female) in female dominated sectors do not report the same level of workplace voice. There is something troubling going on feminised sectors that stifles workers’ voices.

Australia has a strong institutional industrial relations framework. However, it’s also a system that values men’s contribution to the formal economy more than women’s. For a large part of our industrial relations history it was lawful for employers to pay women significantly less (half to two thirds), the rate paid to men. The ‘rationale’ for this discrimination was the ‘male as breadwinner’ trope: men were considered to have greater ‘needs’ as the family provider. Women were framed as dependant on men. While this situation of lawfully inequal pay was remedied through landmark pay cases in the 1970s and1980s, gendered bias remains imprinted on pay setting and industrial relations institutions.

‘Social welfare’, for example, was not covered by an industry award (a document setting out the terms and conditions of employment) until the 1980s, because like many other so-called ‘caring’ jobs, the constituent tasks were not regarded as part of an ‘industry’. Caring was just something women naturally performed. These so-called ‘unskilled’ jobs were poorly categorised and insufficiently documented. The constituent skills and capabilities were not detailed, unlike, for example, a metalworker and other male dominated occupations.

Recent key cases in the Fair Work Commission show the industrial relations system continues to undervalue ‘women’s work’, viewing feminised work as unskilled. In part this is because historically women were seen to have a ‘natural affinity’ with caring, educating and serving others, and hence training requirements were seen as low. (Undervaluation of feminised work).

Applying a gendered lens across all aspects of employment surfaces big problems in the labour market. Lifting the quality of work in highly feminised sectors will net significant benefits for closing national gender gaps and will build women’s economic independence and security.

There is more work to do ensure that highly feminised work is made decent, including building security of employment, eliminating discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace and listening to employee’s voices.

One of the fastest growing and largest employing industries in the Australian labour market is ‘Healthcare and Social Assistance’. This powerhouse sector is critical to the social and economic functioning of our country. It will become even more so as our population ages. Yet, as was exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the lowest paid and most precariously employed people work in this sector. This is especially the case in aged care and disability support.

Australia’s Fair Work Commission recently reappraised the jobs of Australia’s 314,600 aged care workers – 74 percent of whom are female. The Commission considered the value, the nature of the skills involved, and the increasing complexity of the tasks undertaken by workers in this industry.

As a result, aged care workers in Australia will see their pay increase by up to 28.5 percent. In making its decision the Commission acknowledged that “the work of aged care sector employees has historically been undervalued, because of assumptions based on gender.”

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets addressed:

Target 8.5 By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

Target 8.8 Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment

Resources

How can we increase the value attributed to jobs in highly feminised powerhouse sectors of the economy?

Book

- Rae Cooper and Talara Lee, “What’s IR got to do with it? Building gender equality in the post pandemic future of work” in Rönnmar M. and Hayter S. (eds), Making and breaking gender inequalities in work (Cheltenham and Geneva: Edward Elgar, ILO and ILERA, forthcoming)

Articles

- Cooper, R., Mosseri, S., Vromen, A., Baird, M., Hill, E., Probyn, E. (2021). Gender Matters: A Multilevel Analysis of Gender and Voice at Work. British Journal of Management, 32(3), 725-743.

- Cooper, R., Hill, E., Lee, T., Seetahul, S. (2024) Building a more equitable future of work for women in NSW

- Ariadne Vromen, Briony Lipton, Rae Cooper, Meraiah Foley, and Serrin Rutledge-Prior, Pandemic Pressures: Job Security and Customer Relations for Retail Workers (Canberra: Australian National University and University of Sydney Business School, 2021)

- Cooper, R. (2024). Understanding and addressing sexual harassment in the Australian retail sector.

- Rai, S., Brown, B., Ruwanpura, K. (2019) Decent work and economic growth – A gendered analysis. World Development Volume 113, p368 – 380

Website

Professor Rae Cooper, AO is Professor of Gender, Work and Employment Relations. Rae is founding Director of the Australian Centre for Gender Equality and Inclusion at Work.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.