Tooran Alizadeh

Re-imagining Sydney with 3 CBDs: how far off is a Parramatta CBD?

Parramatta has been designated as the central CBD of three future city centres in the Greater Sydney region. haireena/Shutterstock

One of the biggest strategic planning challenges of our time in Australia is to re-imagine the Greater Sydney metropolis with more than one CBD.

My students in the capstone unit of the Master of Urbanism program at the University of Sydney have worked on preparing a strategic plan for a Central City CBD at the heart of the Greater Sydney Region. This work built on the Greater Sydney Region Plan proposed by the Greater Sydney Commission, aka Our Greater Sydney 2056 – A Metropolis of Three Cities.

Greater Sydney Commission

In this plan, the Sydney metropolitan region is re-imagined around three cities:

- Eastern Harbour City – built around the current CBD

- Central River City – built around a new CBD located in Greater Parramatta on the area currently known as Parramatta CBD and Westmead district

- Western Parkland City – built around the growth expected around Western Sydney Airport, Penrith, Campbelltown and Liverpool.

A key objective of the metropolitan plan is to rebalance economic and social opportunity toward Western Sydney and the Central River City, or “Central City”. The vision is for most residents to live within 30 minutes of their job, education, health facilities, and other services.

The first step to fulfil this bold vision is to understand how far Western Sydney is from having its own metropolitan CBD; and to assess how the Central City (in Greater Parramatta) measures up against the existing Sydney CBD, also known as the Harbour City.

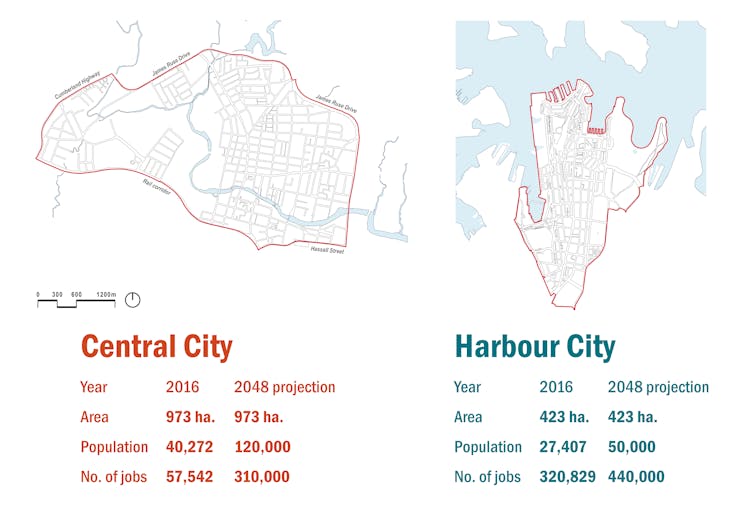

How do the Central City and Harbour City compare?

Image: Jamie van Geldermalsen, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal, Kun Fan, Author provided

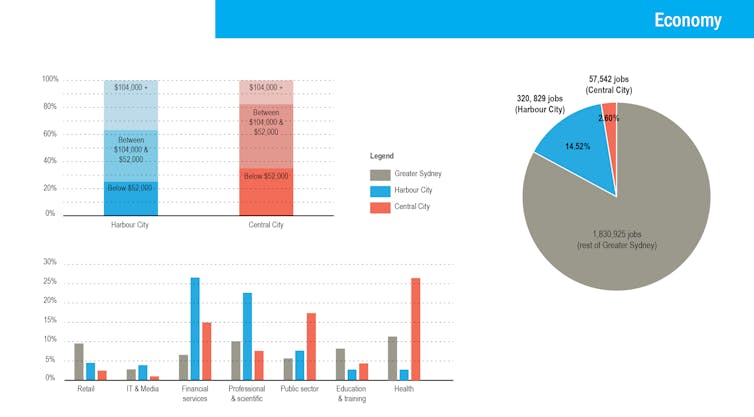

Currently, 2.6% of jobs in Greater Sydney are in Central City, compared to 14.5% located in the established Harbour City. While the Harbour City has many more jobs, the proportion of workers in the health and public sectors is much higher in the Central City – due to the presence of Westmead health precinct. While health will remain important in the Central City’s future, employment opportunities in the financial, tech and legal sectors need to grow significantly if the Central City is to become the next metropolitan centre.

Image: Jamie van Geldermalsen, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal, Kun Fan, Author provided

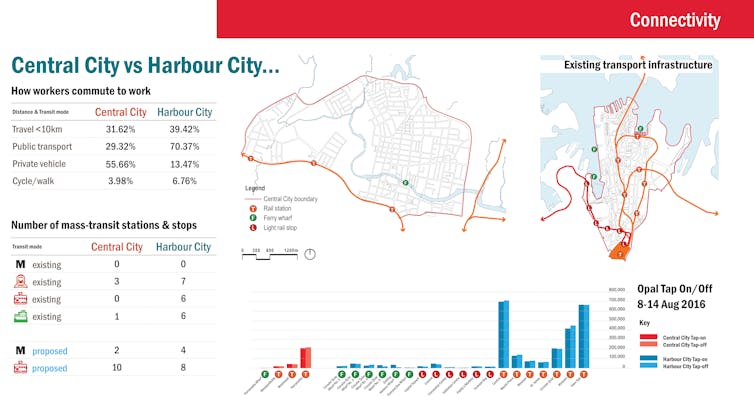

Harbour City offers significantly more regional and local connectivity than Central City. Currently, 70% of Harbour City workers commute to work by public transport and only 13.5% by private vehicle, compared to the Central City’s 30% and 55.65% respectively.

Image: Jamie van Geldermalsen, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal, Kun Fan, Author provided

With the number of trips to Central City predicted to triple or quadruple during morning peak periods from current levels to 2056, forecasts indicate that Central City’s travel-to-work mode split will remain the same. This would lead to increased road congestion, impacting the economy, liveability and sustainability.

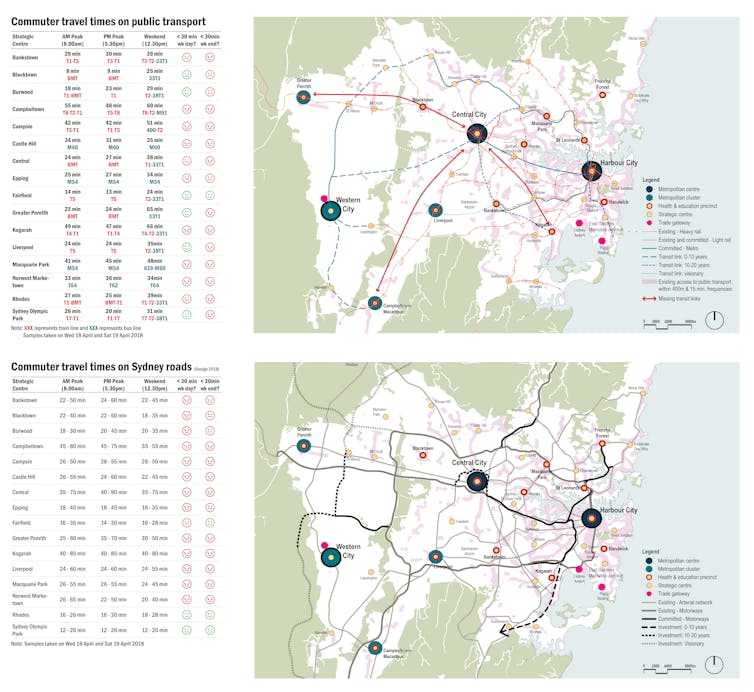

To represent the depth of connectivity problems, Figure 5 shows how long it takes to get to and from the Central City. It assesses travel times between 16 strategic centres and the Central City during peak morning and afternoon periods and on the weekend, for commuters on public transport versus those on the roads.

Image: Jamie van Geldermalsen, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal, Kun Fan, Author provided

The results show the public transport commuters’ travel time from most strategic centres is already greater than 30 minutes. Commute time on the roads varies, going over 30 minutes during the morning peak. Moving commuters around Greater Sydney using the road network is only a temporary measure, as it does not have the capacity to cope with any of the proposed growth.

Image: Jamie van Geldermalsen, Kun Fan, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal, Anjani Rao Gandra, Nithila Rajave, Rachana Chandwani, Tamanna Sultana, Author provided

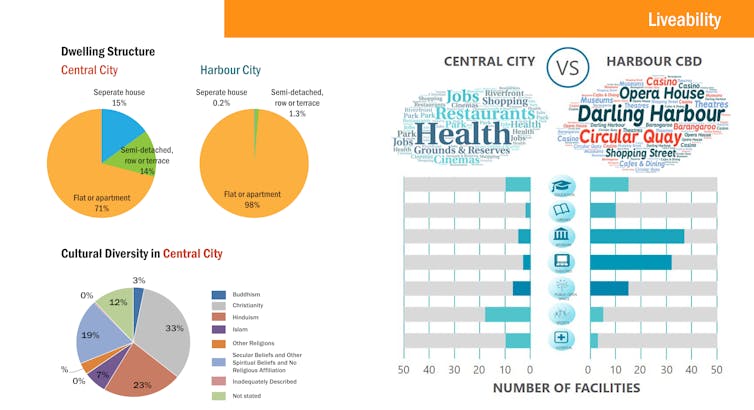

Central City is culturally diverse. More than 140 languages other than English are spoken at home, with more than 65% of people born overseas.

However, social infrastructure to support and celebrate this great diversity is lacking. Access to community facilities such as aged care, child care, schools and non-Christian places of worship are limited. Without investment, the social infrastructure deficit will only be amplified as the population increases.

Harbour City has 11 museums and seven cultural centres; the Central City does not have any museums and only two cultural centres.

The final word

These assessments, from economy, connectivity, and liveability perspectives suggest the Sydney metropolis has a very long and bumpy way to go before we can re-imagine it with more than one CBD. Visionary and bold decision-making, supported by significant investment, is required for the Central City to transition to a metropolitan centre.

This article is inspired by the work of the students enrolled in the Integrated Urbanism Studio for the Master of Urbanism at the University of Sydney. I specifically would like to acknowledge the significant contributions made by Jamie van Geldermalsen, Mile Ilija Barbaric, Rao Umair Afzaal and Kun Fan.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read part two in this series, Reimagining Sydney: this is what needs to be done to make a Central CBD work.

Image: Sandeep Sapkota

Associate Professor Tooran Alizadeh is the co-convener of Smart Urbanism (Research) Lab at the University of Sydney. Her latest book latest book Global Trends of Smart Cities: a comparative analysis of geography, city size, governance and urban planning was published in 2021 by Elsevier. She was recently awarded an ARC Future Fellowship to explore the complex socio-spatial implications of smart city development in India (2022-2026).

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.