The vaccine passport: the most effective way to remove vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine passports are Australia’s ticket out of wide-ranging lockdowns.

Delta has altered the viability of Australia’s current strategy. Continuing a one-size-fits-all approach to risk will inflict more pain on the Australian community than necessary. Differentiating restrictions on rights according to vaccination status will be necessary to reach the final phase of the National Plan to transition Australia to COVID normal.

Vaccine hesitancy has stabilised, according to this survey by the Melbourne Institute: 12% of adult Australians are unwilling to get vaccinated and 9% are unsure. That is enough to reach a 79% vaccination rate and the third phase (out of four) of the National Plan to transition Australia to COVID normal.

The Melbourne Institute’s data also shows that a ban on either travel outside Australia or on going to restaurants and movie theatres would change the minds of 29% of the unsure (i.e., almost 3% overall).

So, these non-monetary incentives are enough to exceed the 80% vaccination rate needed to reach the final phase of the National Plan.

Carrot and stick

A vaccine passport covers activities like going to cafes and restaurants, taking long-distance train journeys, visiting hospitalised family and friends, leaving Australia without an exemption, and returning without having to quarantine in hotels.

The passport is usually in the form of a QR code given to those fully COVID-19 vaccinated, having (paid for) a negative test, or having recovered from the disease.

Throughout the pandemic, both punishments and rewards have been influencing our behaviour. Punishments are supposed to deter us from acting in a particular way, and rewards to encourage certain courses of action. This simple characterisation suggests these techniques work in a straightforward way and are always effective, but that is not the case.

Punishment works, but governments must apply the sanction often, and, preferably, at once. That is easy with behaviour which police can see, such as mask wearing on public transport, but is harder in the case of vaccination uptake for example. The extremity and nature of the penalty play a role too but often the principal factor is the fear and anticipated shame of being caught. Moreover, extreme punishments can cause resistance, especially if people regard them as unfair.

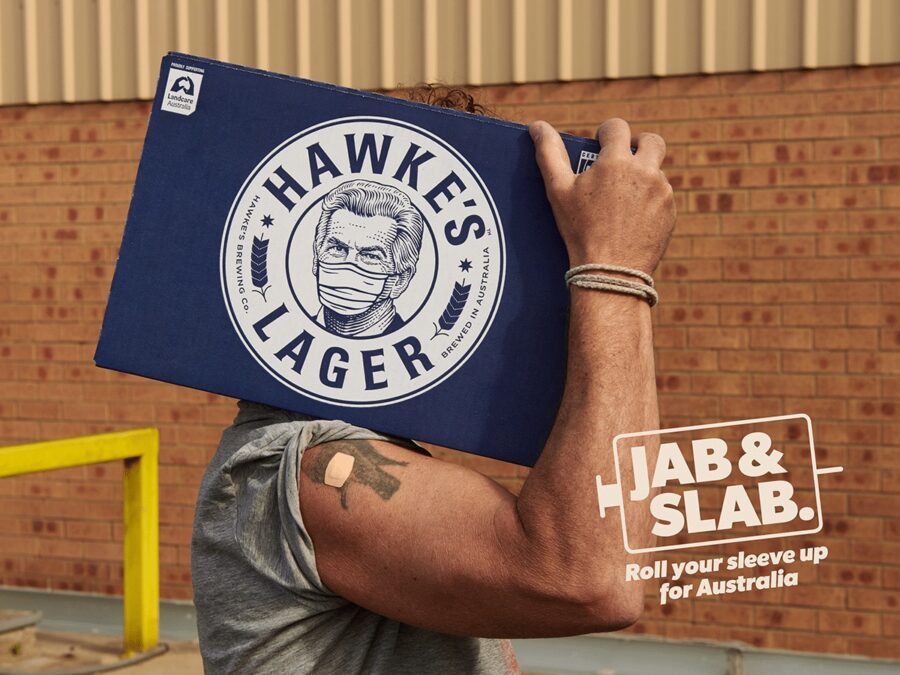

Rewards can also influence vaccination uptake. Amazon, Domain, Telstra, and Zip – are offering bonuses or paid leave to promote vaccine uptake amongst their employees. Burger Urge, Clubs New South Wales, Hawke’s Brewing, and the Prince Alfred Hotel in Port Melbourne are offering free burgers and beers to attract customers to get the jab.

V.I.R.U.S to fight the virus

The academic literature reveals the most effective rewards are like a V.I.R.U.S.: Various, Immediate, Related, Unchanging, and “Story-able.”

A variety of rewards has the greatest effect; for example, permission to go to restaurants and movie theatres as well as travel outside Australia. The more swiftly (immediate) the rewards follow vaccination, the more effective they are likely to be; for example, the vaccine passport is valid from the date of the second vaccination. The same applies to the relatedness of the rewards; if you want hesitant Australians to get vaccinated, you tempt them with what they miss the most due to COVID. Unchanging is another key factor: if people cannot predict with certainty that their vaccination and passport will result in greater freedom, trust is violated. Our research shows that social media allowing storytelling and “naming and praising” exerts a considerable influence too: When people get their vaccine passport, make it easy for them to talk about it, take that selfie, share it online, and let all their friends know.

One potential drawback of the carrot-and-stick approach is our behaviour changes only because of the incentive, not because our underlying attitude has changed. So as soon as the punishments and rewards disappear, we return to our old ways; this is an effect we often see in relation to cash payments, for example. Of course, information about punishments and rewards can make us think about our actions. A vaccination passport would combine the two approaches, making it the best way to endorse vaccination. It can give rise to acceptable practices with the potential to prevent further personal harm.

A vaccine passport is the socioeconomic counterpart of lockdowns, which is why it is unsurprising we see increased adoption of it overseas. For example, they are almost ubiquitous in France’s public and private sectors and in the German private sector, while the German government is increasingly talking about using them as well.

The persuasiveness of COVID-19 vaccination enabling greater freedoms needs to be fully harnessed. Individuals should have their freedoms restored to them once they are fully vaccinated.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Tom van Laer is Associate Professor of Narratology at the University of Sydney. He studies storytelling, social media, and consumer behaviour.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.