Tooran Alizadeh

Turnbull’s government must accept responsibility for delivering an equitable NBN for all Australians

Recently Four Corners asked Australia to consider “What’s wrong with the NBN?”.

Prior to the episode airing, a lot of the debate focused on the NBN’s business model, and that it may not be profitable.

I, however, am not sure if the financial returns need be our biggest concern when referring to public service and critical infrastructure. My answer to the question “what’s wrong with the NBN?” is quite simple: the NBN is inequitable.

A “train wreck”

This week started with a fiery speech delivered by the Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull. He said the NBN was a mistake, blamed the former Labor government for the set up, and described the NBN’s business model as a “calamitous train wreck”.

Turnbull’s remarks triggered a number of responses, including one from former Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd. He attached responsibility of NBN’s failure to the current government, as they “changed the model completely” compared to the original design.

More broadly, the Four Corners program itself created mixed reactions on social media. It was criticised for being “weak”, and not “challenging enough”, but also praised as “exceptional”.

I find it incredibly frustrating to see a national critical infrastructure project diminished to political ping pong. In my opinion, bipartisan commitment is required in order to deliver an equitable NBN for all Australians.

Inequity from the start

Introduced by Labor, the original NBN was announced in April 2009. The plan was to provide terrestrial fibre network coverage for 93% of Australian premises by the end of 2020, with the remaining 7% served by fixed wireless and satellite coverage. In other words, Labor’s NBN was mainly equitable in terms of the advanced technology adopted across the board.

However, research on the early NBN rollout pointed out the issue of timing. Even under the most optimistic estimations, it was going to take over a decade to build the nation-wide infrastructure. So, there were always questions about who was going to get the infrastructure first, and who had to wait over a decade for a similar service.

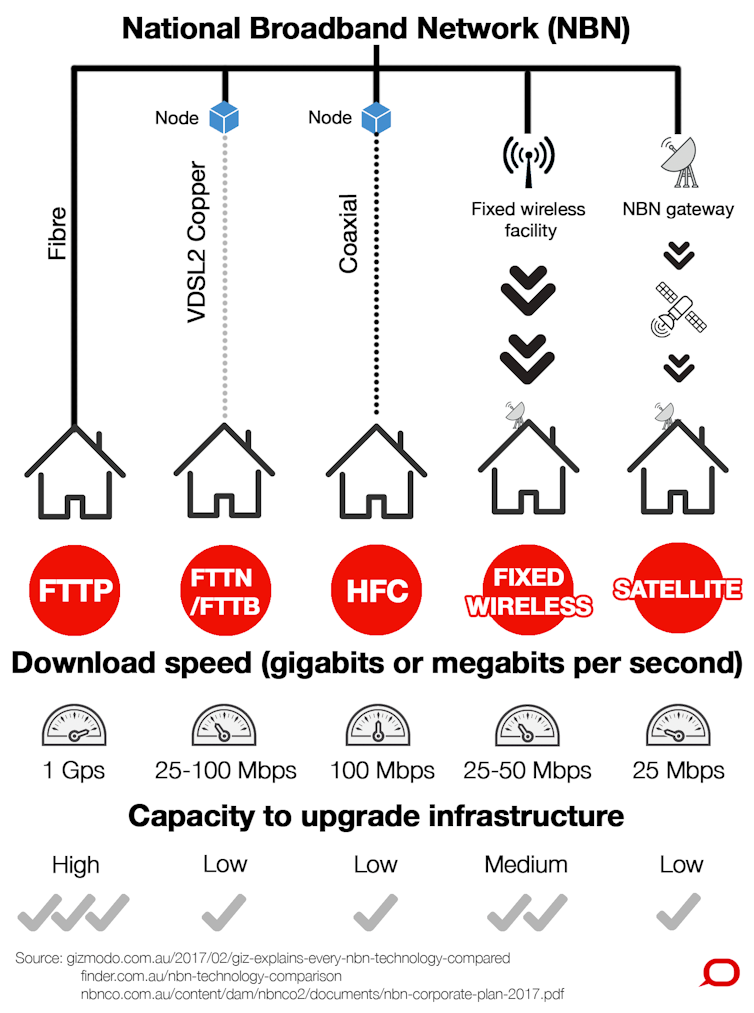

The results of the 2013 Federal election changed the fate of the NBN. The elected Coalition government decided the NBN rollout should transition from a primarily fibre-to-premises model to a mixed-technology model.

FTTP = fibre to the premises; FTTN/FFTB = fibre to the node/basement;

HFC = Hybrid Fibre-Coaxial

This added to the complexity of the NBN, and created new layers in the inequality concerns around the NBN. In the Coalition’s NBN, many could be waiting quite some years and yet still only receive a lower quality level of access to the service.

Inequity in 2017

Now we’re past the halfway point of NBN delivery, and inequality of the service is clear at two levels.

Large scale

Recent research shows there is a clear digital divide between urban versus regional Australia in terms of access to the NBN. Regional Australia is missing out, both in terms of pace and quality of delivery in the mixed-technology model. This pretty much means that WA and NT are the worst off parts of the nation, because of the spread and dominance of regional and remote communities within them.

“Fine grain” scale

As described on Four Corners, mixed-technology NBN within local government areas and neighbourhoods means some people are better off than others.

Some receive fibre-to-premises service while others have fibre-to-node. The quality of the service also depends on how far someone lives and works from a node, which basically suggests even people on the same fibre-to-nodes service could have varied level of (dis)satisfaction with their internet and phone services.

Research published in 2015 captured some of the frustrations on the ground at the local government level. Differing qualities of internet services available were perceived to have direct implications for local economic development, productivity, and sense of community at the local level.

The two layers of NBN inequality mean that while some customers may be happy with their NBN, many experience a frustrating downgrade of service after moving to the NBN. This may help explain the increase in the number of NBN complaints across the nation.

Let’s start moving forwards

Politicising the NBN and blaming one party over another has been part of the national misfortune around the NBN. But, I believe, the inequality of the NBN is part of a bigger trend in infrastructure decision making in Australia that fails to fully account for the socioeconomic implications. Other examples of this trend are seen in major (controversial) transport projects around the nation (e.g. East West Link in Melbourne, WestConnex in Sydney).

Current and future Australian governments must accept responsibility, and find a way forward for the NBN that is built on the notion of equitable service.

We can start with questions such as who needs the service the most, and who can do the most with it. These two questions refer to the social inclusion and productivity implications of the NBN.

The NBN, as a publicly funded national infrastructure project, has to be equitable to be a truly nation building platform. As long as it is failing some, it is failing us all as a nation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Please refer to The Conversation’s republishing guidelines before republishing this article.

Associate Professor Tooran Alizadeh is the co-convener of Smart Urbanism (Research) Lab at the University of Sydney. Her latest book latest book Global Trends of Smart Cities: a comparative analysis of geography, city size, governance and urban planning was published in 2021 by Elsevier. She was recently awarded an ARC Future Fellowship to explore the complex socio-spatial implications of smart city development in India (2022-2026).

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.