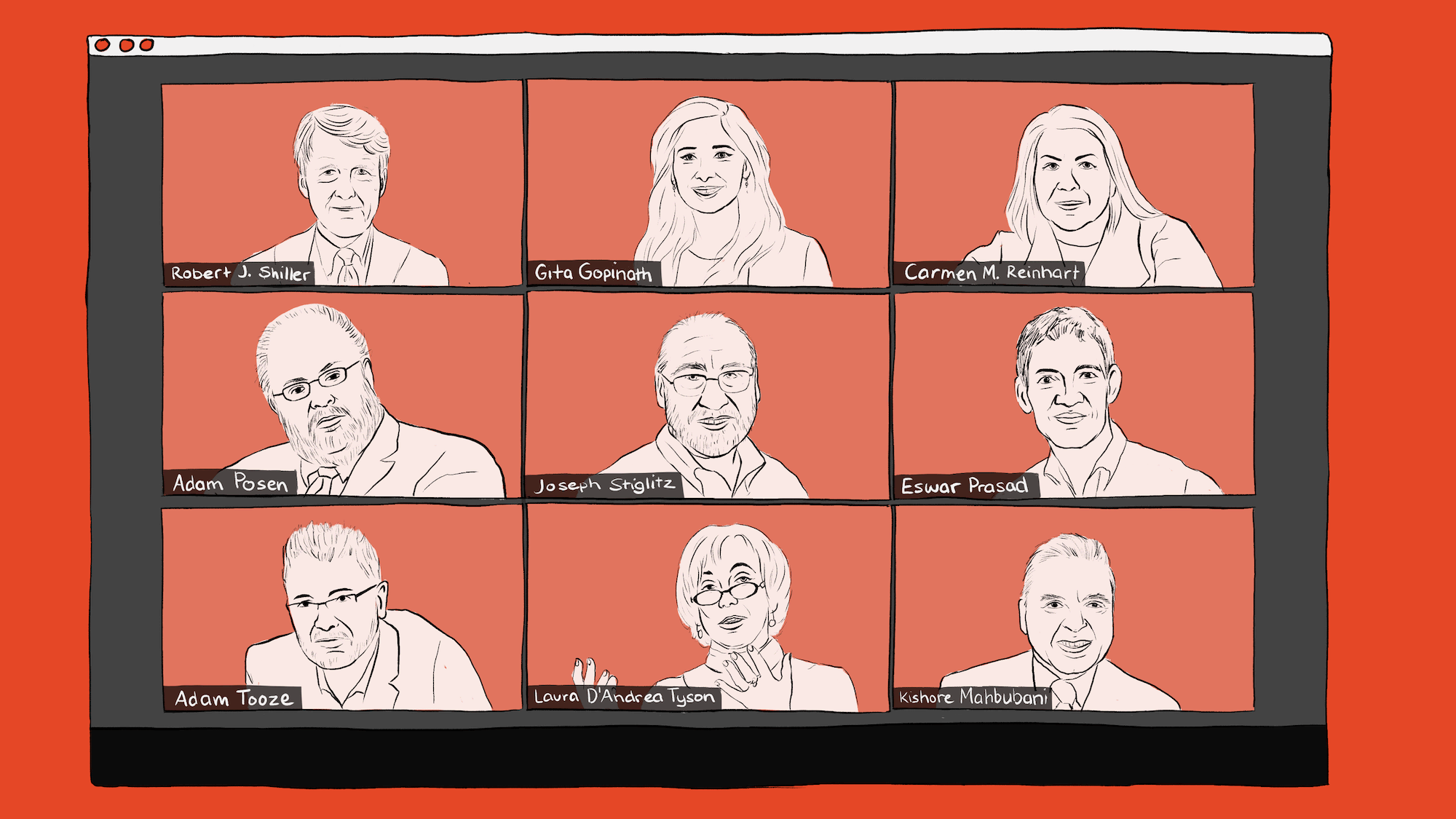

Joseph E Stiglitz, Robert Shiller, Gita Gopinath, Carmen Reinhart, Adam Posen, Eswar Prasad, Adam Tooze, Laura D. Tyson and Kishore Mahbubani

How the economy will look after the coronavirus pandemic

After many weeks of lockdowns, tragic loss of life, and the shuttering of much of the global economy, radical uncertainty is still the best way to describe this historical moment.

Will businesses reopen and jobs come back? Will we travel again? Will the flood of money from central banks and governments be enough to prevent a deep and lasting recession, or worse?

This much is certain: The pandemic will lead to permanent shifts in political and economic power in ways that will become apparent only later.

To help us make sense of the ground shifting beneath our feet, nine leading thinkers weigh in with their predictions for the economic and financial order after the pandemic.

We need a better balance between globalisation and self-reliance

Economists used to scoff at calls for countries to pursue food or energy security policies. In a globalised world where borders don’t matter, they argued, we could always turn to other countries if something happened in our own. Now, borders suddenly do matter, as countries hold on tightly to face masks and medical equipment, and struggle to source supplies. The coronavirus crisis has been a powerful reminder that the basic political and economic unit is still the nation-state.

The coronavirus crisis has been a powerful reminder that the basic political and economic unit is still the nation-state.

To build our seemingly efficient supply chains, we searched the world over for the lowest-cost producer of every link in the chain. But we were short-sighted, constructing a system that is plainly not resilient, insufficiently diversified, and vulnerable to interruptions. Just-in-time production and distribution, with low or no inventories, may be capable enough of absorbing small problems, but we have now seen the system crushed by an unexpected disturbance.

We should have learned the lesson of resilience from the 2008 financial crisis. We had created an interconnected financial system that seemed efficient and was perhaps good at absorbing small shocks, but it was systemically fragile. If not for massive government bailouts, the system would have collapsed as the real estate bubble popped. Evidently, that lesson went right over our heads.

The economic system we construct after this pandemic will have to be less shortsighted, more resilient, and more sensitive to the fact that economic globalisation has far outpaced political globalisation. So long as this is the case, countries will have to strive for a better balance between taking advantage of globalisation and a necessary degree of self-reliance.

This wartime atmosphere has opened a window for change

There are fundamental changes that happen from time to time—often during times of war. Though the enemy is now a virus and not a foreign power, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a wartime atmosphere in which such changes suddenly seem possible.

Though the enemy is a virus and not a foreign power, the pandemic has created a wartime atmosphere in which fundamental changes suddenly seem possible.

This atmosphere, with narratives of both suffering and heroism, is spreading with the disease. Wartime brings people together not only within a country, but also between countries, as they share a common enemy like the virus. Those who live in advanced countries can feel more sympathy with those suffering in poor countries because they are sharing a similar experience. The epidemic is also bringing us together in countless Zoom get-togethers. Suddenly the world seems smaller and more intimate.

There is also reason to hope that the pandemic has opened a window to creating new ways and institutions to deal with the suffering, including more effective measures to stop the trend toward greater inequality. Perhaps the emergency payments to individuals that many governments have made are a path to a universal basic income. In the United States, better and more universal health insurance might just have been given new impetus. Since we are all on the same side in this war, we may now find the motivation to build new international institutions allowing better risk-sharing among countries. The wartime atmosphere will fade again, but these new institutions would persist.

The real risk is politicians exploiting our fears

Over only a few weeks, a dramatic chain of events—tragic loss of life, paralysed global supply chains, interrupted shipments of medical supplies between allies, and the deepest global economic contraction since the 1930s—has laid bare the vulnerabilities of open borders.

People may self-assess their individual risks and decide to curtail travel indefinitely, reversing 50 years of rising international mobility.

If support for an integrated global economy was already declining before COVID-19 struck, the pandemic will likely hasten the reassessment of globalisation’s costs and benefits. Firms that are part of global supply chains have witnessed firsthand the risks inherent in their interdependencies and the large losses caused by disruption. In future, these firms are likely to take greater account of tail risks, resulting in supply chains that are more local and robust—but less global. In emerging markets, whose embrace of globalisation included a steady opening to capital flows, we risk seeing capital controls being reimposed as these countries scramble to shield themselves from the destabilising forces of the sudden economic stop. And even as containment measures gradually come off worldwide, people may self-assess their individual risks and decide to curtail travel indefinitely, reversing half a century of rising international mobility.

The real risk, however, is that this organic and self-interested shift away from globalization by people and firms will be compounded by some policymakers who exploit fears over open borders. They could impose protectionist restrictions on trade under the guise of self-sufficiency and restrict the movement of people under the pretext of public health. It is now in the hands of global leaders to avert this outcome and to retain the spirit of international unity that has collectively sustained us for more than 50 years.

Another nail in the coffin of globalisation

World War I and the global economic depression in the early 1930s ushered in the demise of a previous era of globalisation. Apart from a resurgence of trade barriers and capital controls, an important explanation for this demise is the fact that more than 40 percent of all countries at the time entered default, cutting many of them off from the global capital markets until the 1950s or much later. By the time World War II ended, the new Bretton Woods system combined domestic financial repression with extensive controls of capital flows, with little resemblance to the preceding era of global trade and finance.

Pandemic-induced recessions may be deep and long—and as in the 1930s, sovereign defaults will likely spike.

The modern globalization cycle has faced a series of blows since the financial crisis of 2008-2009: a European debt crisis, Brexit, and the U.S.-China trade war. The rise of populism in many countries further tilts the balance toward home bias.

The coronavirus pandemic is the first crisis since the 1930s to engulf both advanced and developing economies. Their recessions may be deep and long. As in the 1930s, sovereign defaults will likely spike. Calls to restrict trade and capital flows find fertile soil in bad times.

Doubts about pre-coronavirus global supply chains, the safety of international travel, and, at the national level, concerns about self-sufficiency in necessities and resilience are all likely to persist—even after the pandemic is brought under control (which may itself prove a lengthy process). The post-coronavirus financial architecture may not take us all the way back to the preglobalization era of Bretton Woods, but the damage to international trade and finance is likely to be extensive and lasting.

The economy’s preexisting conditions are made worse by the pandemic

The pandemic will worsen four preexisting conditions of the world economy. They will remain reversible through major surgery but turn chronic and damaging absent such interventions. The first of these conditions is secular stagnation—the combination of low productivity growth, a lack of private investment returns, and near-deflation. This will deepen as people stay risk-averse and save more following the pandemic, which will persistently weaken demand and innovation.

Second, the gap between rich countries (along with a few emerging markets) and the rest of the world in their resilience to crises will widen further.

Economic nationalism will increasingly lead governments to shut off their own economies from the rest of the world.

Third, partly as a result of flight to safety and the apparent riskiness of developing economies, the world will continue to be over-reliant on the U.S. dollar for financing and trade. Even while the United States becomes less attractive for investment, its attraction will increase relative to most other parts of the world. This will lead to ongoing dissatisfaction.

Finally, economic nationalism will increasingly lead governments to shut off their own economies from the rest of the world. This will never produce complete autarky, or anything close to it, but it will reinforce the first two trends and increase resentment of the third.

More than ever, the world looks to central bankers for deliverance

The economic and financial carnage wrought by the pandemic could leave deep scars on the world economy. Central banks have stepped up to the challenge by tearing up their own rulebooks. The U.S. Federal Reserve has bolstered financial markets with asset purchases and provided dollar liquidity to other central banks. The European Central Bank has declared “no limits” to its support of the euro and announced massive purchases of government and corporate bonds, and other assets. The Bank of England is financing government spending directly. Even some emerging-market central banks, such as the Reserve Bank of India, are considering extraordinary measures—all risks be damned.

Central bankers, once considered cautious and conservative, have shown they can act with agility, boldness, and creativity.

Fiscal stimulus by governments, on the other hand, has proved to be politically complicated, cumbersome to implement, and often difficult to target where the need is greatest.

Central bankers, once considered cautious and conservative, have shown they can act with agility, boldness, and creativity in desperate times. Even when political leaders are unwilling to coordinate policies across borders, central bankers can act in concert.

Now and for a long time to come, central banks have become entrenched as the first and main line of defense against economic and financial crises. They may come to rue this immense new role and the unrealistic burdens and expectations it will impose on them.

The normal economy is never coming back

As the lockdowns began, the first impulse was to search for historical analogies—1914, 1929, 1941? Since then, what has come ever more to the fore is the historical novelty of the shock we are living through. There is something new under the sun. And it is horrifying.

The economic fallout defies calculation. Many countries face a far deeper and more savage economic shock than they have ever previously experienced. In sectors like retail, already under fierce pressure from online competition, the temporary lockdown may prove to be terminal. Many stores will not reopen, their jobs permanently lost. Millions of workers, small-business owners, and their families are facing catastrophe. The longer we sustain the lockdown, the deeper the economic scars, and the slower the recovery.

The longer we sustain the lockdown, the deeper the economic scars, and the slower the recovery.

What we thought we knew about the economy and finance has been radically disturbed. Since the shock of the 2008 financial crisis, there has been a lot of talk about the need to reckon with radical uncertainty. We now know what truly radical uncertainty looks like.

We are witnessing the largest combined fiscal effort since World War II, but it is already clear that the first round may not be enough. There are few illusions about the unprecedented acrobatics that central banks are performing. To deal with the accumulated liabilities, history suggests some radical alternatives, including a burst of inflation or an organized public default (which would not be as drastic as it sounds if it affects government debts held by central banks).

If the response by businesses and households is risk-aversion and a flight to safety, it will compound the forces of stagnation. If the public response to the debts accumulated by the crisis is austerity, that will make matters worse. It makes sense to call instead for a more active, more visionary government to lead the way out of the crisis. But the question, of course, is what form that will take and which political forces will control it.

Many lost jobs will never return

The pandemic and subsequent recovery will accelerate the ongoing digitalization and automation of work—trends that have eroded middle-skill jobs while increasing high-skill jobs during the last two decades and contributed to the stagnation of median wages and rising income inequality.

Many low-wage, low-skill, in-person service jobs, especially those provided by small firms, will not return with the recovery.

Changes in demand, many of them accelerated by the economic dislocation wrought by the pandemic, will change the future composition of GDP. The share of services in the economy will continue to rise. But the share of in-person services will decline in retail, hospitality, travel, education, health care, and government as digitalisation drives changes in the way these services are organised and delivered.

Many low-wage, low-skill, in-person service jobs, especially those provided by small firms, will not return with the eventual recovery. However, workers providing essential services such as policing, firefighting, health care, logistics, public transportation, and food will be in greater demand, creating new job opportunities and increasing the pressure to raise wages and improve benefits in these traditionally low-wage sectors. The downturn will accelerate the growth of nonstandard, precarious employment—part-time workers, gig workers, and workers with multiple employers—leading to new portable benefits systems that move with workers and broaden the definition of employer. New low-cost training programs, digitally delivered, will be required to provide the skills required in new jobs. The sudden dependence of so many on the ability to work remotely reminds us that a significant and inclusive expansion of Wi-Fi, broadband, and other infrastructure will be necessary to enable the accelerating digitalisation of economic activity.

A more China-centric globalisation

The COVID-19 pandemic will accelerate a change that had already begun: a move away from U.S.-centric globalisation to a more China-centric globalisation.

The COVID-19 pandemic will accelerate a change that had already begun: a move away from U.S.-centric globalization to a more China-centric globalization.

Why will this trend continue? The American population has lost faith in globalisation and international trade. Free trade agreements are toxic, with or without U.S. President Donald Trump. By contrast, China has not lost faith. Why not? There are deeper historical reasons. Chinese leaders now know well that China’s century of humiliation from 1842 to 1949 was a result of its own complacency and a futile effort by its leaders to cut it off from the world. By contrast, the past few decades of economic resurgence were a result of global engagement. The Chinese people have also experienced an explosion of cultural confidence. They believe they can compete anywhere.

Consequently, as I document in my new book, Has China Won?, the United States has two choices. If its primary goal is to maintain global primacy, it will have to engage in a zero-sum geopolitical contest, politically and economically, with China. However, if the goal of the United States is to improve the well-being of the American people—whose social condition has deteriorated—it should cooperate with China. Wiser counsel would suggest that cooperation would be the better choice. However, given the toxic U.S. political environment toward China, wiser counsel may not prevail.

This article was originally published in Foreign Policy. Read the original article.

Please note that rights to this article belong to the original publisher, please contact them for permission to republish.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Professor Stiglitz teaches at the Business School at Columbia University. He was awarded the 2001 Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics.

Robert Shiller is Professor of Economics and Finance at Yale University. He was awarded the 2013 Nobel Memorial Prize in economics.

Professor Gopinath is the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund.

Carmen Reinhart is Professor of the International Financial System at the Harvard Kennedy School. She was previously the IMF’s Deputy Director.

Adam Posen is the President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Eswar Prasad is Professor of Trade Policy at Cornell University. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Adam Tooze is a Professor of History and the Director of the European Institute at Columbia University.

Professor Laura D. Tyson is faculty director at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. She is an expert on trade and competitiveness.

Kishore Mahbubani is a Distinguished Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.