Quo Vadis air travel after COVID-19?

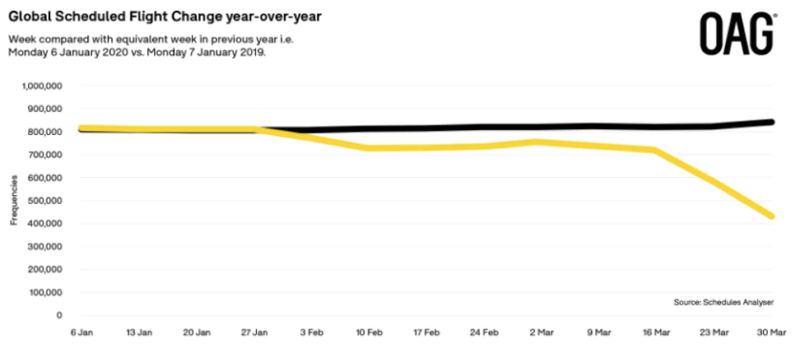

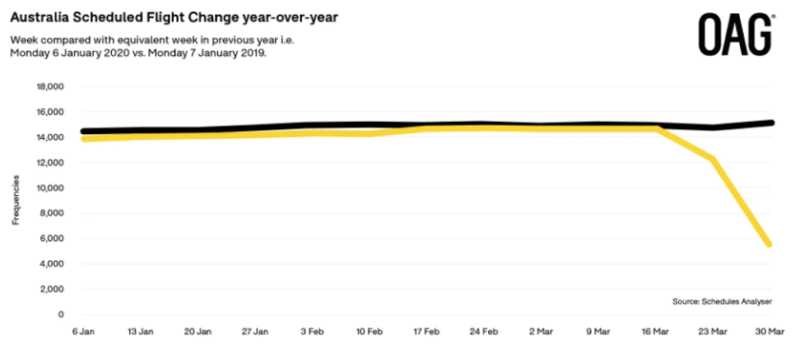

Air travel has been hit hard by COVID-19. At a global level, scheduled flights have halved and have fallen by 65% in Australia. It is estimated that 50 million jobs will be lost world-wide in the travel and tourism industry. What then is to become of the sector post crisis?

Air travel has been hit hard by COVID-19. At a global level, scheduled flights have halved and have fallen by 65% in Australia. It is estimated that 50 million jobs will be lost world wide in the travel and tourism industry.

Airlines, despite exponential growth in passenger numbers and revenue over the past decades, will be particularly affected and many may not survive the crisis. Looking forward, there is no clear trigger for an easing of travel restrictions as countries will be reluctant to open borders without clear signs that the threat has passed. Moreover, there is no clear indication yet as to how the preferences of both tourists and business travellers may change or how their budgets might be affected by a prolonged global recession. As a result, we may see less competition and a contraction in the airline industry, yet a functioning airline sector is essential for the country’s many tourism and travel-related jobs.

Two likely futures need to be considered. First, airlines, much like banks after the global financial crisis, might be required to keep much higher cash reserves for resilience. Second, we might see much greater levels of government involvement as the result of bailout action, either through regulation or state ownership.

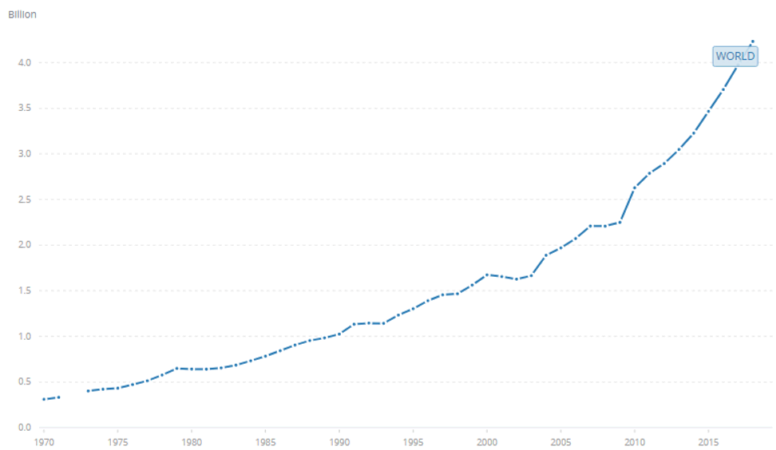

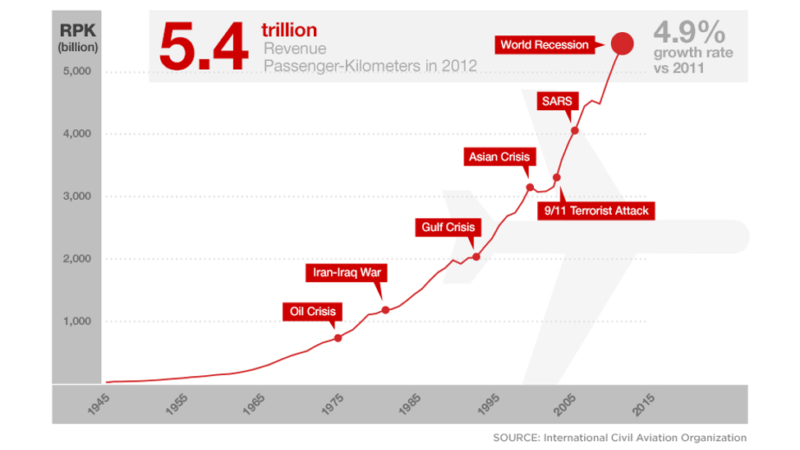

In the current spirit of exponential graphs, prior to the spread of COVID-19, the global airline industry itself exhibited growth at an exponential rate. The world has never been more connected and people have never enjoyed more freedom to travel the globe, a fact that contributed to the swift spread of the virus.

A recent report by the World Travel and Tourism Council estimated that global travel and tourism accounted for 10.4% of global GDP, supported 319 million jobs (10% of total global employment), with one in five jobs over the last 5 years being created in the travel and tourism sector.

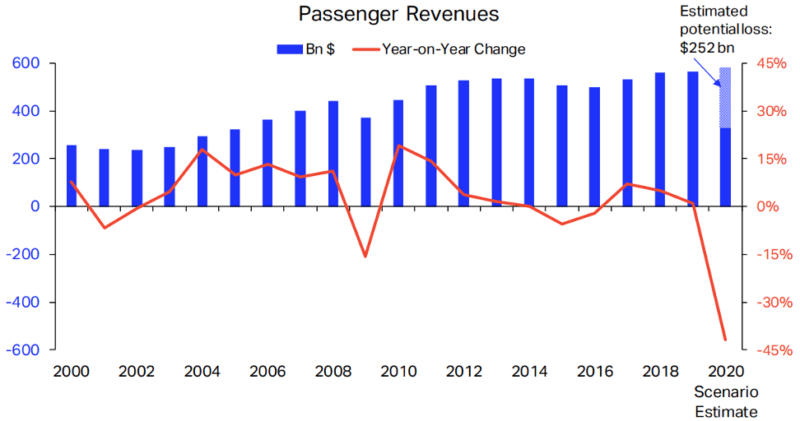

Historically the airline industry has been robust with revenue, also growing exponentially over time despite pandemics, terrorism and recession.

Perhaps the last time the air travel sector saw comparable widespread groundings was in 2010 with the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, which led to the suspension of flights in Europe from the 15th to the 23rd of April, with intermittent shutdowns following that period. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) estimated that the total loss for the airline industry was around US$1.7 billion (£1.1 billion, €1.3 billion).

During this time, several airlines made calls to their respect governments for compensation and support, while others in the industry felt that at the time “the airlines that are around today have been toughened by adversity, the weak players have already been found out by the market.”

The situation today

The COVID-19 outbreak is unlike anything else we have seen before. Looking at the latest global statistics on scheduled flights, we can see what is now a halving of scheduled flight movements as countries close their borders and similarly place limits on domestic travel. The gap between scheduled movements this year compared to last year will likely increase, as the Northern hemisphere moves into what would be the summer holiday period. And the reduction of scheduled flights in Australia has been even more dramatic (second figure below).

Latest modelling by IATA indicate that passenger revenues will be $252 billion lower this year compared to 2019 and revenue passenger-kilometres will decline by 38% in year-over-year terms.

Looking ahead

Moving forward, what might this mean for global travel and tourism, and the airline sector? Firstly, the future is unclear, what exactly will trigger the freeing international movement is not known. Countries will be reluctant to open their borders and risk a re-emergence of COVID-19 without definitive evidence that the threat has eased.

Perhaps the most definitive trigger for relaxation of global travel restrictions will be the advent of a vaccine but that is at least 12 months away, ignoring the further time it would take to mass produce a vaccine on the scale that would be required.

There is very little indication as to how individuals will react. While some may be less inclined to travel, previous graphs have shown that growth in international travel continues unabated by shocks of many types. Previous research has shown that travellers react to external threats in the short-term, but over time those preferences have so far reverted back to pre-existing thresholds.

However, the recent growth in travel has been predicated on the fact that international travel was becoming more affordable, thanks to new technology and fiercer competition in the industry. Yet, with a prolonged global recession there may be less competition in the sector moving forward and what was once affordable may no longer be so, and the number of competing airlines may well be less.

Many airlines are going to be in financially precarious positions. While revenue has grown exponentially, many airlines have used the gains during that period to engage in share buy-backs1. Many airlines now face an immediate and critical liquidity challenge; IATA estimate that most have less than three months liquidity and that simply surviving this extended period of turmoil will be no simple task for the majority.

Airlines in Australia are not immune, with the industry receiving a $715million support package as a result of COVID-19. Virgin Australia has asked the Australian government for a $1.4 billion loan that could be converted to shares in the airline in certain circumstances. Qantas, in a somewhat tit-for-tat response is asking for a $4.3 billion dollar loan arguing that it is about three times as large as Virgin. In the US, President Trump has also flagged that support for the airline industry is likely.

The debate on assistance is mixed. Individual airlines operate with very thin margins due to huge capital investments on expensive and depreciating assets, and have no sustainable competitive advantage. Equally, a functioning airline sector is important for supporting Australian tourism and travel jobs, many of which exist in regional parts of the country.

Consequently, there is a strong public good argument for supporting the airline industry. However, what will rankle many is that airlines are adept at gaining public support in times of crisis, but are able to privatise gains when times are good.

Possible Futures

From this there are likely two futures that airlines might need to consider. Firstly, much like the banking sector was forced to keep greater reserves of liquidity as a result of the global financial crisis, airlines could be encouraged to keep greater reserves of liquidity to be more resilient to shocks to the sector.

Secondly, we may see a future where the government is increasingly more involved in the airline sector either via regulation or direct ownership. For example, Alitalia is now fully owned by the Italian government as a result of COVID-19 and indeed, state ownership of airlines is not at all unusual. Air China, Air France, Air New Zealand, Cathay Pacific, China Airlines, Emirates, Etihad Airways, Finnair, Malaysia Airlines, Qatar Airways and Singapore Airlines are a handful of carries that are either fully or in part owned by the government.

Lastly, with regards to the Australian tourism industry, it is likely that preference for international travel may be suppressed, or unaffordable, for some time thus raising the attractiveness of domestic travel. Following the bushfires there were many well received campaigns to travel and buy local, and the sector will need to recapture that momentum and sense of Australian-ness. But again, the ability for Australians to begin travelling domestically is still unclear. It may well lie in the success of “flattening the curve” rather than an outright identification of a vaccine.

Footnotes

[1] In the US, six of the larger airlines spent 96% of their free cash flow on stock buybacks over the past 10 full years through 2019.

This is part of a series of insights related to Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its impact on business.

Matthew is Professor of Decision Making and Choice at The University of Sydney Business School in the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies. His research focusses on behavioural economics and modelling.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.