Anastasia Globa

VR is transforming how buildings are made

You’re on a tour of your brand-new office.

You love the way the windows are positioned to catch the morning sun – but worry it will be too hot in the middle of the day at the height of summer. The building’s architect takes note, and the windows are lowered and sun-responsive louvres added the entire building façade.

These structural changes take just a few minutes to rework – the tour is a virtual one. Construction has not commenced, so design alterations are inexpensive to render.

Augmented and virtual reality are not just for gamers. Architects can use virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to demonstrate what a building will look like, how it will sound, how its surfaces will feel, and even how it will smell (I’ll get to that later). We can demonstrate how the space will sound if there are 10 people, or 100, in the space. How will the soundscape change if the floor is made of wood? Or concrete? Or carpeted?

Advances in VR and AR are helping architects design more efficient and sustainable buildings. Despite the best intentions of architects and designers, many design solutions do not work efficiently, or as planned. People tend to occupy spaces as they please, not necessarily in the ways designers intend or expect.

Buildings and other architectural spaces, especially public and business venues, are often designed without any direct input from future occupants. VR simulations allow for rapid and cost-effective qualitative assessment of design options, and inform decision-making in architecture.

Try to remember the last time you personally had input into the design of a space you work or live in.

And even when future occupants are involved, it might not be easy for non-design professionals to properly assess the quality of a design proposal just by looking at plans, sections, elevations, or renders.

We no longer need to rely on the individual capability of people to read plans or imagine the spaces based on the pictures or verbal descriptions.

Now we can actually enable people to experience them. Recent advances in VR make it possible to provide not post-occupancy evaluation but to advance towards pre-occupancy evaluation of built spaces.

Getting away from nature is bad for humans

Global urbanisation, where people move to live in the cities, continues to rise dramatically. Currently more than 50% of the world’s population lives in urban areas. By 2050 this number is expected to be around 70%.

People living in highly urbanised areas become increasingly separated from nature and natural environments. People spend most of their time in generic artificially constructed settings, both at home and at work.

Recent studies have shown that reduced human-nature interaction has a strong negative effect on our health and wellbeing. Being constantly exposed to artificial and homogeneous lighting, temperatures, forms and materials is not good for us. VR/AR can help connect office and apartment dwellers to nature.

Biophilic design – it’s bucolic

In architecture, biophilic design refers to a set of principles reinforcing the human-nature connection, using the perspective of multi-sensory experiences – what we see, what we hear, what we feel, and what we smell.

Biophilia, is much more complex than hanging a picture of mountains on your wall or having a plant sitting on your desk. To test different biophilic design settings and attributes would take a lot of money and time, this also might significantly delay project development. That’s where VR comes in to save the day – and costs.

VR – beyond the visual

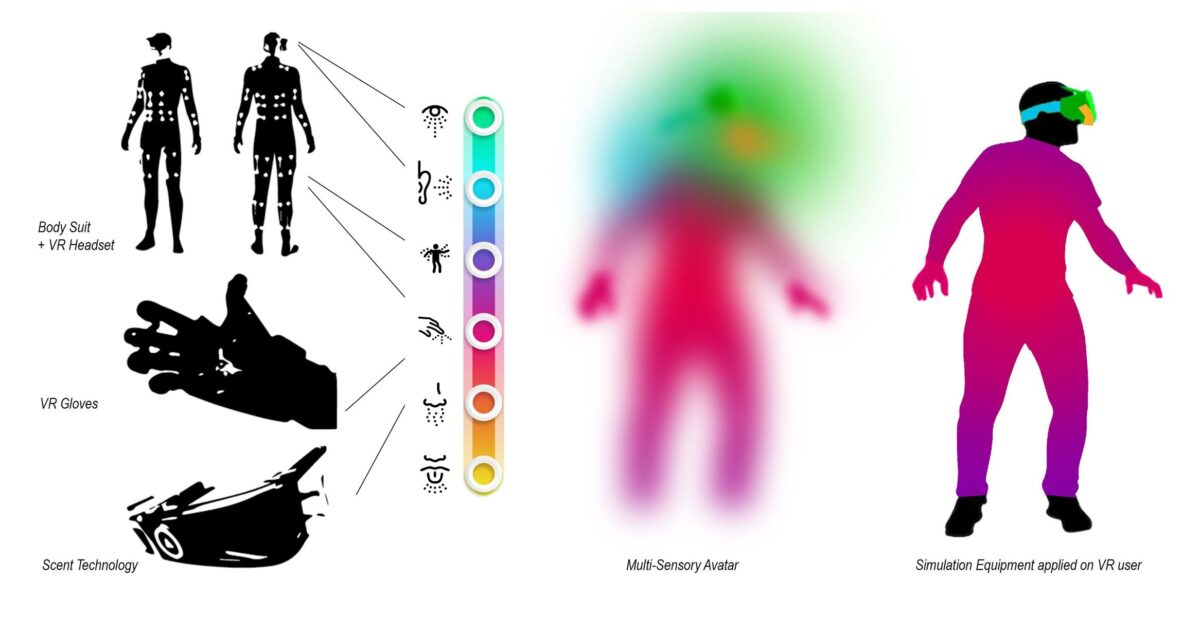

The vast majority of current VR applications predominately focus only on visual experiences. It is all about what we see. All other sensory simulations that include auditory, tactile, thermal, olfactory and taste are extremely limited, or non-existent.

My aim is to enable the experience of both tangible and intangible aspects of space in VR and AR using a range of dynamically changing conditions, simultaneously engaging with as many human senses as we possibly can.

The latest research suggests that providing 3D sound, haptic, thermal and olfactory inputs in a virtual environment can improve the sense of presence.

Integrating all multi-sensory aspects at once is the ultimate goal.

On the nose, wearable scent devices

Currently scent wear cartridges can simulate three categories of smells: Nature (pine forest, earthy dirt, flowers): Vignette, created to support relaxation and well being projects (energise, waterfall, marshmallows, pretty random but very distinctive smells): Less Pleasant Odours (a real title) that is used to train firefighters, police and medical staff and includes the smell of bodily fluid, fire/smoke and other potentially triggering smells that might be encountered in extreme situations.

Expensive? Very. Between $4,500 to $24,000 per year.

Touching what is not there

VR gloves with little clip-on pockets for each finger carry the haptic feedback screen on the sensitive part of the finger pad along with an exoskeleton that also provides feedback.

VR gloves keep our minds immersed, bringing physical sensations into virtual reality. The ability to touch and feel virtual objects. Tactile displays for each finger emulate sensations and create the perception of solid object texture and various surface types.

An exoskeleton creates resistance and gently pulls fingers during grasping movements, stopping the hand around a virtual object. This provides the perception of shape, and size and simulates the vibration of equipment.

Again, at a cost of between $20,000 to $124,000, VR gloves and the integration pack are one of the most expensive gadgets we have in our lab.

Digital taste

Ok, this may not be so relevant to architecture and certainly there is no commercially available product available. What can an architect do with a lickable screen device, that when inserted into the mouth can recreate taste sensations associated with food via microscopic particles activated by an electric charge? I’m keen to find out.

What’s next? Watch (smell, hear, taste and touch) this space

The overarching aim of what I am working on is to enable the experience of both tangible and intangible aspects of space in VR using a range of dynamically changing conditions; simultaneously engaging with as many human senses as we possibly can.

To test a multi-sensory VR approach, we have created several VR prototypes. We have already tested the integration of spatial awareness, and 3-dimensional spatial soundscapes, as well as creating visually dynamic environments where users could not only make changes to the environment on the fly (like changing design options, walking or teleporting around or making coffee using a coffee machine, turning a light on and off) but also simulate temporal aspects, geolocation, and weather. We even simulated different levels of clutter in the office. Because realistically nothing stays empty for long, during a building’s occupation.

The overall objective is to achieve multi-sensory VR to allow for a more participatory and inclusive design process, resulting in more efficient and sustainable solutions.

Image: James Yarema

Anastasia is a Lecturer in Computational Design and Advanced Manufacturing at The University of Sydney. She is a member of the CoCoA research lab, an ECR Ambassador at the Sydney Nano Institute, and President of CAADRIA. Her design and research projects often involve the use of various digital fabrication technologies.

Share

We believe in open and honest access to knowledge.

We use a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives licence for our articles and podcasts, so you can republish them for free, online or in print.